|

Click

on a Topic Below |

| Home » Policy » Implications of Uncertainty on Integrated Assessments and Cost-Benifit Analysis of Climate Change |

|

|

|

|

| Implications of Uncertainty on Integrated Assessments and Cost-Benefit Analysis of Climate Change |

Previous: Uncertainty and SustainabilitySeveral economic studies, most notably Nordhaus's pioneering DICE model (Nordhaus, 1994b) have concluded that stringent measures to control emissions of CO2 would be very costly even when the benefits of reducing the emissions (i.e., avoided climatic changes) are taken into account. Nordhaus finds it optimal to allow emission rates to increase threefold over present levels in this century alone. Several other studies have reached similar results (e.g., Manne et al. (1995) and Peck & Teisberg (1993)). However, these results have been challenged by a growing number of studies, including Cline (1992), Azar and Sterner (1996), Roughgarden & Schneider (1999), Schultz & Kastings (1997), and Howarth (2000), who find that much stronger cuts in emissions are defensible on economic efficiency grounds alone. Many of them have shown that the outcome of any climate change cost-benefit analysis is very sensitive to the choice of discount rate. Some have argued that when dealing with intergenerational issues, the rate of discounting should fall over time (e.g., Azar & Sterner (1996), Heal (1997), Weitzman (2001)), while others have analyzed the issues within the framework of overlapping generation models (see e.g., Howarth (2000)). In addition to discounting, some of the divergence in results can be attributed to choices of parameter values or even structural relationships that can be improved with more research within economics, ecology, and climatology. However, such improvements will not suffice to bridge all of the gaps in results. Rather, some differences ultimately stem from disagreements on certain value-laden key parameters and modeling choices. Azar (1998) identifies four crucial issues for cost-benefit analysis of climate change: the treatment of low-probability but catastrophic impacts, the valuation of non-market goods, the discount rate, and the choice of decision criterion. He shows that (i) ethically controversial assumptions have to be made about each of these aspects, (ii) the policy conclusions obtained from optimization models are very sensitive to these choices, and (iii) studies that find that minimal reductions are warranted have made choices that tend to reduce the importance of the most common arguments in favor of emission reductions. Including Risks of Catastrophes in Cost-Benefit AnalysisThe strong focus throughout this website has been on uncertainty and how that might affect the level and timing of mitigation policies. As we have noted, the complexity of the climate system implies that surprises and catastrophic effects could well unfold as the climate system is forced to change, and that the larger the forcing, the more likely there will be large and unforeseen responses. While the scenarios recently suggested by a Pentagon report and "The Day After Tomorrow", a new global warming movie (see Contrarian Science for details), are way overblown in forecasting exteremly severe abrupt change in the short-term (next few decades), there is a distinct possibility of such events being induced by human actions over the next generation or two, even if the actual unfolding of the severe change doesn't occur for another century or so. How, then, might we deal with low- or unknown-probability, high-impact events in cost-benefit analysis? Two different approaches emerge, as Schneider and Azar (2001) note:

Confident estimation of the probabilities and costs of true catastrophic surprises is, by definition, impossible, as a true surprise (and therefore its probabilities) is unknown. In addition, the higher the stakes of a problem, the more contested the science behind it, so many policy audiences are likely to be skeptical from the start. This means that they are very difficult, to say the least, to include in integrated assessments or benefit-cost analyses of climate change. But the possibility of such events is an important driver for climate policy and must be considered. Moreover, even though we may not be able to envision the nature of a true surprise, we can fathom the conditions that would give rise to a greater likelihood of surprises — what Schneider et al. (1998) labeled “imaginable conditions for surprise.” Nordhaus attempted to consider extreme events by assuming that global economic damage from climate change was proportional to the temperature change raised to the power of twelve (Nordhaus, 1994b, p. 115). Under this method, Nordhaus arrived at an optimal abatement level of 17%, a target stricter than the 9% abatement level advocated by the Kyoto Protocol but less ambitious than what some might expect given the extreme nature of the damage function. Nordhaus came to this optimization level under what are called deterministic conditions. The optimizer (global policymaker, for example) knows exactly where the very steep increase in costs begins and can therefore take action when needed to remain within the safe zone. Cost-benefit optimization with a low-probability, high impact event was also analyzed in a study conducted by the Energy Modeling Forum (Manne et al., 1995). Uncertainty was assumed to be resolved by 2020, and very little near-term hedging was found to be optimal. One key reason for this result is that the probability for a catastrophic event was assumed to be only 0.25%, which is rather low in relation to other assessments (IPCC 2001c, Section 10.1.4.1). Several papers have tried to model the interconnectedness of learning, uncertainty, and irreversibility into the economic analysis of climate change. Kolstad notes that “the literature on irreversibilities tells us that with learning, we should avoid decisions that restrict future options” (Kolstad, 1996a, p. 2). He then sets off to look at greenhouse gas stock irreversibility versus capital stock irreversibility and concludes that the irreversibility of investment capital has a larger effect than the irreversibility of greenhouse gas accumulation. A similar result is obtained by Ulph and Ulph (1997). The intuitive explanation for this result is that while an investment in renewable energy cannot easily be reversed (if it proves that we do not really need to reduce the emissions), emissions are reversible in the sense that emitting one unit today can in principle be compensated for by emitting one less unit at some time in the future (Kolstad, 1996 Note 1). However, this result is limited in scope. Kolstad (1996a, p. 14) recognizes that he has “not examined irreversible changes in the climate or irreversibilities in damage. Such irreversibilities are of real concern to many concerned with climate policy.” In a separate paper, he writes “of course, one may still wish to restrict emissions today to avoid low-probability catastrophic events” (Kolstad 1996b, p 232). However, many other studies support the idea that significant near-term abatement is essential to avoiding major climatic damages and possible catastrophe. Fisher (2001) and Narain & Fisher (2003) develop a model in which the risks of catastrophic events are endogenous and directly correlated to how many greenhouse gases are emitted. They find, contrary to the results of Kolstad (1996a) and Kolstad (1996b), that the climate irreversibility effect might actually be stronger than the capital investment irreversibility effect, not weaker. The Fisher analyses offer qualitative insights into the relative strengths of the different irreversibility arguments, but they do not offer any quantitative “real world” numbers in regard to optimal abatement levels. Gjerde et al. (1999) conclude that “the probability of high-consequence outcomes is a major argument for cutting current GHG emissions.” Mastrandrea and Schneider (2002) show that by including the risk of a complete shut down of THC in the Nordhaus DICE model, many very different “optimal emission trajectories” with much more stringent emissions controls are obtained, especially if a low discount rate or very high enhanced damages are applied (see the “Cliff diagram”). This literature is valuable because it demonstrates that perceptions of what constitutes an “optimal” policy depend on structural assumptions and the numerical values of parameters that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, to confine to narrow ranges. In some cases, like that of the discount rate, the parameters depend on value judgments; and in other cases — the threshold for THC collapse — they depend on physical phenomena that are difficult to predict confidently. That benefit-cost analysis is an important tool that can be used to guide policymakers into making informed decisions concerning trade-offs in a resource-scarce world is not disputed here. But when applied to large-scale interregional and intergenerational problems characterized by deep uncertainty and doubt about accurate optimization strategies, there is a considerable risk that this approach will mislead those not aware of the many limitations and implicit assumptions in most conventional cost-benefit calculations available in the climate literature. The principal concern is that the seemingly value-neutral language of benefit-cost analysis — mathematics — will lead some policymakers into believing that value-neutral policy conclusions can be drawn from seemingly objective analyses. Another concern is that the uncertainty about climate damages is so large that it renders any cost-benefit analysis (CBA) using a single climate damage function of little use. Roughgarden and Schneider (1999) have argued that a probability distribution (see Probability distributions (f(x)) of climate damages) must be used to display the wide range of opinions in the literature about what climate damages might be (given some degree of climate change), which then provides a probability distribution of “optimal policies” as an output of the CBA rather than a misleading single “optimal” policy. This reframes the debate as a risk-management exercise where a range of policy actions could all be “optimal” depending on whether the high or low damage estimates turn out to be correct. At present, it seems that cost-benefit analyses applied to the problem of global climate change can largely justify any emission reduction targets, marginal or substantial. The latter will be particularly justifiable if nasty surprises are taken into account. Uncertainty and Energy Systems InertiaWRE expressed concern that a premature retirement of existing capital stock would be expensive. (This is similar to the Kolstad argument highlighted earlier in this section.) They argue that deferring abatement would avoid, or at least reduce, this cost and make the transition to a low-CO2-emitting future less costly. Wigley et al. (1996), as well as a number of economists, have argued that any long-term stabilization target could be met more cost-effectively by reducing less now and more later on. Taken to the extreme, this view has been twisted to mean that we should not reduce anything at all now and compensate for it by introducing more stringent reductions later on. The lower future abatement costs would largely be derived from the fact that future costs are discounted, and that postponing emission reduction will give us time to develop new and more advanced energy technologies and plan the restructuring of the energy system so that premature retirement of existing energy capital is avoided. Optimization models looking at the interaction between the economy and the energy system have been used to demonstrate such conclusions numerically. But counterarguments can be raised. For one, capital is replaced continuously. If typical energy capital has a lifetime of, say, forty years, this means that roughly 25% will be replaced every decade. There is even greater turnover in the auto industry, where there is larger potential for rapid energy efficiency improvements than in, say, power plants and the steel industry Note 2 . If we exploit this routine capital stock turnover, we may avoid a renewed buildup of long-lived, carbon-intensive technologies and thus a potential future premature retirement of capital stock (particularly if more rapid rates of future reductions are demanded to meet increasingly stringent abatement targets, as discussed in Grubb (1997)). Ha-Duong et al. (1997) used stochastic optimization techniques to determine the optimal hedging strategy given uncertain future carbon constraints. They operated under the assumption that there are costs associated not only with the level of abatement, but also with the rate of change of the abatement level. (The idea was that this would capture capital stock turnover issues.) Uncertainty was assumed to be resolved by the year 2020. The findings in the paper by Ha-Duong et al. (1997) suggested that early abatement, which could entail capital stock replacement, was economically efficient. Lovins and Lovins (1997) make a similar argument, noting that businesses can "profitably displace carbon fuels," mainly through energy savings due to increased efficiency. A similar approach was taken by Yohe and Wallace (1996), but they reached the opposite conclusion. The differing conclusions are largely due to the choice of stabilization constraint. Ha-Duong et al. (1997) assumed a stabilization target of 550 ppm, with symmetric probabilities around this goal (2.5% for 400 ppm and 750 ppm, 10% for 450 ppm and 700 ppm, 20% for 500ppm and 650 ppm, and finally, 35% for 550 ppm) Note 3, whereas Yohe & Wallace (1996) chose an uncertainty range of 550 - 850 ppm. These modeling results were clearly sensitive to the ultimate stabilization target. If a low stabilization target is chosen, stringent near-term abatement is found cost-efficient. If a high stabilization target were chosen, less early abatement would be required. Thus, optimal near-term policies depend on considerations about the long-term target. It would have been very interesting if optimization models with perfect foresight about what was going to happen over the next hundred years had called for similar near-term policies regardless of the stabilization target. They do not. Therefore, any judgment about the cost-efficiency of near-term abatement targets is contingent on the (too often implicit) choice of ultimate stabilization target However, this stabilization target is uncertain and controversial. We know with high confidence that there are certain results of climate change will cause negative impacts on society, such as a rising sea levels, but given the complexity of the climate system, other unexpected impacts cannot be ruled out. Some of them might be more serious than the changes that have high confidence ratings assigned to them. It is likely that views and decisions about the ultimate stabilization targets will change over time. Clearly, new knowledge and information and the resolution of some uncertainty will drive this process (see Rolling Reassessment). However, it will also be driven by each generation's values and sense of responsibility towards nature, future generations, the distribution of “winners and losers” of both climate impacts and policies, and perceptions about what “dangerous climatic change” means. And, equally important, prevailing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere will have a strong impact on each generation's debate over which stabilization target society should select. The higher the concentration, the more difficult it is to convince policymakers that a low target should be chosen. The main reason why 550 ppm is being discussed now is that governments and policy analysts see it as feasible, in contrast to, say, 400 ppm. Azar and I argued that targets that have been discarded as impossible, such as 350 ppm, might still be on the agenda today had carbon abatement or low-carbon technological development been initiated in 1970. Some early capital stock turnover now may thus be one way of avoiding, rather than causing, the premature replacement of the capital stock built in the hope that significant abatement might not prove necessary (that is, if it turns out that low stabilization targets are warranted). Of course, as with all the tools that have been discussed, major uncertainties are inherent in these citations as well. Nonetheless, the insights these authors provide through their analyses are worth consideration, even if the numerical results do not carry high confidence levels. Technological ChangeWRE also argued that technical progress would bring down the cost of alternative technologies over time. This, they claimed, would make it more cost-effective to defer emission abatement to the future when it would be cheaper. Critics of this position argue that technological change is not simply an autonomous process that takes place regardless of policies chosen. Rather, it is the result of a complex web of factors involving prevailing and expected prices, consumer values, taxes and regulations, and technology policies. R&D for systems that are less carbon-intensive will not progress rapidly just because policies encouraging it are implemented. In addition to policy, carbon-free technology development also depends on the creation of markets for emerging technologies and an expectation that the price of carbon will rise over time. Grubb (1997) pointed out “it is in steering the markets that governments can have the biggest impact on technology development.” Similarly, Brown and Parkinson (2000) note that market mechanisms provide incentives and flexibility but also promote competition. As an analogy, we need active training, not relaxation, to get into shape to run a marathon. In addition, Austin (1997) notes “it is ironic that proponents of delay place so little faith in near-term technological improvements driven by market and policy signals and so much faith in long-term technological improvement driven by nothing at all.” There is overwhelming evidence that energy policies are of critical importance to the development of alternative technologies (see Azar & Dowlatabadi, 1999 and Interlaboratory Working Group, 2000). There is also much evidence that energy policy can contribute to the lack of development of greener technologies. Think of the fact that refrigerators became less energy efficient per unit of refrigerated volume between 1955 and 1970 (but this trend was reversed in response to the energy crises of the 1970s -- see Rosenfeld, 2003, slide 3) and that energy efficiency improvements in small cars have been more than counteracted by heavier cars and more powerful engines so that the overall energy use per kilometer has gone up in the U.S., mostly from SUVs (although California has been quite aggressive in its pursuit of more efficient, cleaner vehicles — see "Automakers Drop Suits Over Clean-Air Regulation"), and remained roughly constant over the past twenty years in many other countries. These steps backwards will not be reversed without strong policy. For example, recent advancements in fuel cell technologies have been driven by Californian air quality legislation. Rapid growth in wind, photovoltaic (PV), and hydrogen (see Dale Simbeck's hydrogen presentation) technology largely depends on government efforts to steer markets through subsidies. In a March 2004 lecture for Capitol Science evenings at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, John Holdren, Director of the Science, Technology, and Public Policy program at Harvard, suggested that only through improved technology would it be possible to:

Holdren also stated that only through improved policy can we hope to:

But implementing such policy is another story. I agree with Holdren that environment is the hardest part of the energy problem, energy is the hardest part of the environmental problem, and the energy - environment - economy nexus is the hardest part of the sustainable prosperity problem. If the world decided to defer implementation of the Kyoto Protocol for another twenty years, it is likely that private and government research, development, and demonstration of carbon-efficient technologies would drop rather than increase. (As Holdren notes, the Bush Administration is right to say that improved technology will be key to reducing climate change risks cost-effectively, but wrong to be spending so little to make it happen.) Under certain circumstances, markets can work somewhat well to encourage "greening". As gasoline prices have skyrocketed in the US, for example, so has the demand for hybrid cars, while large vehicle sales are beginning to fall (see "Hybrid-car popularity shifts into overdrive"). While it is true that the government has intervened and offered a tax break to those who purchase hybrids, it also appears that the market is effectively changing consumer opinion, though the percentage of hybrid vehicles on the road is still small. However, as is becoming increasingly clear, policies encouraging abatement and renewable energy and creating markets conducive to such technology are often what spurs market-based change. As King, 2004 says, "...the market cannot decide that mitigation is necessary, nor can it establish the basic international framework in which all actors can take their place." Markets cannot deliver optimal outcomes when environmental externalities and public goods are not priced in. This is the task of responsible government. In light of declining R&D budgets for renewables and the absence of strict abatement policies, growth in the use of renewables looks grim. In fact, government R&D spending on renewables in the OECD countries dropped by more than 50 percent between 1980 and 1995. In the US, the drop was close to 60 percent (see Margolis & Kammen, 1999a). For more discussion of technological possibilities and current research gaps, see "One Recipe for a (Mostly) Emissions-Free Economy". Subsidies. The most prominent alternative to abatement policies is R&D subsidies targeting decarbonizing technologies and the creation of niche markets (either through subsidies or specific legislation requiring that a certain percentage of an energy market be derived from renewable energy). However, economic justifications for subsidy policies relative to more direct climate policies like a carbon tax are difficult to justify on efficiency grounds unless there are clear preexisting market inefficiencies that could be corrected by such subsidies (e.g., Schneider and Goulder, 1997). Schneider and Goulder (1997) suggest that the most cost-effective policy may well be a combination of targeted technology development subsidies and abatement actions, not subsidies alone. Creating markets for emerging technologies (e.g., through green certificates or renewable energy portfolios) may be equally important, but that is not seen as a function of R&D. Technological change — Exogenous or Endogenous? As I've mentioned, Wigley, Richels and Edmonds (WRE, 1996) presented data on various stabilization targets for atmospheric CO2 ranging from 350-750 ppm and argued that no significant abatement was seen as desirable over the next couple of decades. They contended that it would not only be possible, but also more cost-effective, to defer emission abatement. They argued, using three economic points and one physical one, that it would be more cost-effective to continue on current emission trajectories, which would arrive at the same long-term stabilization concentrations as cutting emissions earlier on would.Although the divergence between the Wigley, Richels and Edmonds (WRE, 1996) paper and its critiques was more related to the relative weight which the different sides put on “market pull” versus “R&D push", it should be noted that these issues never entered into the climate policy models used to assess the WRE argument. In most energy systems models, technological change is generally assumed to be exogenous (see Azar & Dowlatabadi (1999) for a review of technical change in integrated assessment models). In these models, carbon-free technologies generally improve and become cheaper over time regardless of the amount of R&D occurring, the presence of niche markets, or the strength of carbon abatement policies Note 4. Therefore, the argument that early abatement is necessary to develop the required technologies is not well captured by most models (see Sanstad, 2000). Two interesting exemptions are the studies by Mattsson & Wene (1997) and Goulder & Schneider (1999). Both have endogenized research and development in cost-effectiveness models and showed that early abatement is warranted because it buys down the costs of technologies in the future. In the absence of such abatement, technological progress occurs primarily in conventional technologies (i.e., not renewables). By allowing energy R&D to compete with other economic sectors in a highly aggregated general equilibrium model of the US economy, Goulder and Schneider (1999) — hereafter GS — postulate that a $25/ton carbon tax would likely dramatically redistribute energy R&D investments from conventional to what are now considered non-conventional sectors, thereby producing induced technological changes (ITC) that would eventually lower long-term abatement costs. Another method for encouraging "green" technologies is restricting financing of projects such as oil and coal (or oil- and coal-fired) developments. The World Bank has proposed doing just that, though it still has not finalized its stance on the issue (see "Proposal to Limit Oil and Coal Projects Draws Fire"). The idea was suggested by Emil Salim, a former Indonesian environmental minister who was asked to write the report by James Wolfensohn, president of the World Bank. In the report, Salim states that the Bank should promote clean energy by ending financing of coal and oil projects altogether by 2008, though the World Bank is unlikely to support such a stringent proposal. It is hoped that such a move will also produce ITC that lowers abatement costs. The degree of cost reduction depends on a variety of complicated factors, to be briefly described below. Unfortunately, most integrated assessment models (IAMs) to-date do not include any endogenous ITC formulation (or if they do, it is included in a very ad hoc manner). Thus, insights about the costs or timing of abatement policies derived from IAMs should be viewed as quite tentative. However, even simple treatments of ITC or learing-by-doing (LBD) (e.g. Grubb et al. (1995); Goulder and Schneider (1999); Dowlatabadi (1996); Goulder and Mathai (1999), Grubler et al. (1999)) can provide qualitative insights that can inform the policymaking process, provided the results of individual model runs are not taken literally given the still ad hoc nature of the assumptions that underlie endogenous treatments of ITC in IAMs. Goulder and Schneider (1999) demonstrate that there may be an opportunity cost related to ITC. Even if a carbon tax did trigger increased investment in non-carbon technologies (which, indeed, does happen in the GS simulations), this imposes an opportunity cost to the economy, as it crowds out R&D investments in conventional energy and other sectors. The key variable in determining the opportunity cost is the fungibility of human resources. If all knowledge-generating members of the labor force are fully employed, then increased R&D in non-carbon technologies will necessarily come at the cost of reduced research on conventional technologies. In other words, there would be a loss of productivity in conventional energy industries relative to the baseline no-carbon-policy case. However, this imposes only a short-term cost that is paid early in the simulation. The benefits, lower costs for non-conventional energy systems, are enjoyed decades later, and they are assumed to more than offset the preliminary costs. With conventional discounting, that means the early costs from the crowding out are likely to have more impact on present value calculations than the later benefits, which are heavily discounted (at 5% per year in GS) because they occur many decades in the future. A similar effect might be realized due to transition costs. For example, engineers cannot switch from one industry to another, e.g. from oil to solar power, seamlessly; in general, they require retraining, which involves a cost. On the other hand, if there were a surplus of knowledge-generating workers available in the economy, then the opportunity costs of such transitions could be dramatically reduced. Similarly, if a carbon policy were announced sufficiently far in advance (e.g., 5-10 years), then industries could invest more leisurely in training workers in the skills necessary for non-carbon energy systems without massively redeploying existing knowledge generators. This would offset much of the opportunity cost that GS calculates would surface with fully employed R&D workers and no advanced notice of the carbon policy. When GS ran a model with the assumption that there was no opportunity cost associated with R&D, which implies that there is a surplus of R&D resources in the economy and their focus can be switched without cost to non-carbon-based technologies, they found that ITC positively affects GDP. In this case, ITC is efficiency-improving and is thus is a below-zero-cost policy. However, in the presence of 1) perfectly functioning R&D markets, and 2) a scarcity of knowledge-generating resources (e.g., all capable engineers already fully employed), when a carbon tax is imposed without notice, the presence of ITC by itself is unable to make carbon abatement a zero-cost option. In the GS model, it can actually increase the gross costs to the economy of any given carbon tax. But with ITC, more abatement is obtained per unit of carbon tax, so the net cost per unit carbon reduction is lower with than without it. This also means that the carbon tax required to meet a specific carbon abatement target is lower with ITC. Finally, as a general note of caution, policymakers need to be aware of underlying or simplifying assumptions when interpreting IAM results and know whether they exclude or include treatments of ITC. Schneider (1997b) offered the following list of concerns about ITC in general, and GS in particular:

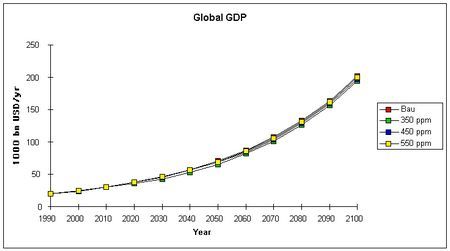

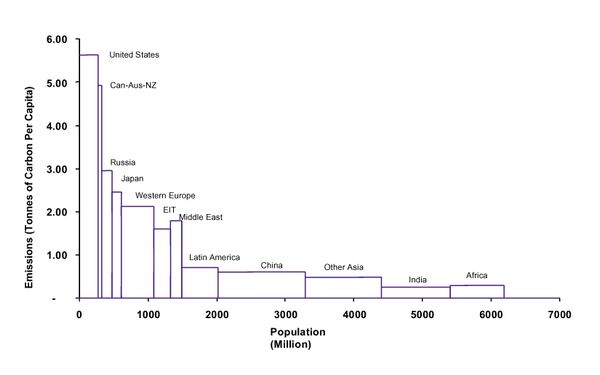

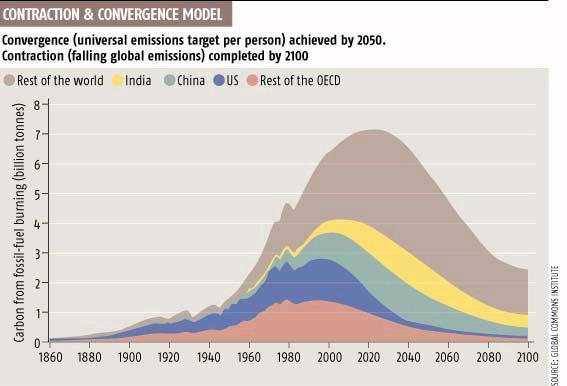

Political Feasibility and Credible SignalsThe economic arguments for postponing emission reductions have sometimes been distorted so that it seems it would be economically efficient to postpone reductions indefinitely. But, since there is an upper limit on the cumulative amount of CO2 that we may emit for some specified target concentration (i.e., 550 ppm), we do have to start reducing net emissions at some point. And even if the economic arguments for deferral were convincing to all parties involved in the debate, one would still need to discuss the political feasibility of that action and its effect on emission trajectories. Suppose that we choose to defer emissions reductions until the year 2020, at which point large reductions would be needed. It is difficult to believe that the policymakers serving in 2020 would feel committed to uphold the stabilization target that we set for them today. Rather, they may consider the preplanned stabilization target too difficult to reach — citing the costliness of premature retirement of capital stock, for instance — and instead opt to increase the stabilization target and further delay abatement. Deferring reductions is extremely disadvantageous in that it reduces the probability of reaching the preplanned stabilization target. This aspect has been formally modeled by Dowlatabadi (1996), who concludes: “under specific conditions, delay can lead to a sequence of control measures which increase the probability of noncompliance.” A real-life example of this paradigm is the Swedish debate about nuclear power. In 1980, a referendum and a subsequent decision by the Parliament concluded that Swedish nuclear reactors should be phased out by the year 2010. However, decisions to phase out nuclear power have been delayed based on arguments similar to the second and third arguments in WRE. The longer Sweden defers the initiation of the phase-out program, the more difficult it has become to meet the 2010 complete phase-out date. Consequently, it now seems unlikely that nuclear power will be phased out by the year 2010. The analogy suggests that delay is likely to breed further delay and thus frustrate the implementation of policies. As WRE note, the political leaders of the future are unlikely to accept the stringent abatement requirements made for them by this generation of policymakers unless there really are low-cost and low-carbon energy systems available in the future. But this will require the inducement of R&D in the near-term through some combination of direct subsidies and abatement policies. Endogenizing Preferences and Values. Similar to technological change, preferences and values are almost always assumed to be exogenous in economic analyses. However, values change and are endogenous to, among other things, decisions taken in the society. Arguing that a transition to a low carbon emitting energy system is necessary would encourage a greater social acceptance for, say, carbon taxes, than if decision-makers argue that it is “optimal” to postpone reductions. Early abatement increases awareness about the potential risks associated with carbon emissions, including health risks and the benefits to health of eliminating or lessening those risks (see Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology (BEST), 2002). This awareness builds social acceptance for carbon taxes, energy efficiency standards, or other policies and measures. An increasing acceptance implies a higher willingness to pay for renewables, which in turn means that the costs of the transition will be lower. All this takes time. Opting only for delay will seriously reduce both current and future levels of abatement. Other Considerations - What is in the Baseline? The concept of baseline emissions is ambiguous for various reasons. A wide range of near-term policies could result in essentially the same near-term emission paths but produce diverging long-term trajectories. A policy package that aims at improving a nation's infrastructure for transportation, the expansion of natural gas distribution (including hydrogen-compatible systems), and the development of solar cells, would not produce any major near-term emission reductions, but would be instrumental for achieving more stringent reductions further into the future. Such a package could be warranted, but there is a risk that such a policy would be judged cost-inefficient based on the perception that near-term abatement is not cost-effective. It is for this reason important to distinguish between actual emission reductions and action to reduce the emissions (see Azar, 1998; Schneider & Goulder, 1997; and Janssen & de Vries, 2000). Another issue related to baseline ambiguities is that of “no regrets.” WRE argued in favor of no-regrets policies in their article, but in their graph depicting emission trajectories, the suggested “optimal” emission trajectories contained business as usual emissions for several decades. In most, if not all, energy-economy models, markets are assumed to be in Pareto equilibrium (i.e., there are no market imperfections), and, therefore, any abatement is by definition associated with a positive cost. It would appear in this situation that the potential for "no regrets" actions is zero, but in reality, there are indications that sizeable no-regrets options are available Note 5, and cost-effectiveness considerations suggest that these should be seized earlier rather than later. One might also interpret these energy-economy models as if the no-regrets options are already in the baseline trajectory, but this can be misleading since the implementation of many “no regrets" options requires specific policies if they are to be tapped. Is the Cost of Stabilizing the Atmosphere Prohibitive? Although the technical feasibility of meeting low atmospheric CO2 stabilization targets has been demonstrated (see IIASA/WEC (1995), IPCC (1996c), Azar et al. (2000), and many others for targets around 400 ppm), there is still concern about the economic costs of realizing such targets. The more pessimistic economists generally find deep reductions in carbon emissions to be very costly — into the trillions of dollars. For instance, stabilizing CO2 at 450 ppm would, according to Manne & Richels (1997), cost the world between 4 and 14 trillion USD. Other top-down studies report similar cost estimates (see IPCC 2001c, chapter 8). Nordhaus argued a decade ago that “a vague premonition of some potential disaster is insufficient grounds to plunge the world into depression” (Nordhaus, 1990). Azar and I would agree with Nordhaus if that premise were true, but we challenged the premise in 2001. More recently, Linden claimed that stabilization of atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases “would essentially destroy the entire global economy” (Linden (1996), P. 59). Similarly, Hannesson (1998), in his textbook on petroleum economics, argues, “if the emissions of CO2 are to be stabilized or cut back, at least one of two things must happen. Either the poor masses of the world will continue their toil in poverty or the inhabitants of the rich countries will have to cut back their standards of living to levels few would be willing to contemplate." Statements along these lines may have contributed to the concern of the former and present Bush Administrations that carbon abatement might “threaten the American way of life.” Although many are skeptical about CO2 abatement on the ground of cost-effectiveness, we must note, paradoxically, that the results of even the most pessimistic economic models support the conclusion that substantial reductions of carbon emissions and several fold increases in economic welfare are compatible targets. Schneider (1993a), in a comment on the Nordhaus DICE model, pointed out that the “draconian” 20 percent emissions cut (20 percent being the cut advocated at the time by many environmental groups and some governments) that DICE calculated was both too costly and economically inefficient only delayed a 450 percent rise in per capita income by a decade, from simulated year 2090 to about 2100. Schneider argued that a ten-year delay in achieving a phenomenal 450 percent growth in income per head was surely a politically palatable planetary “insurance policy” to abate global warming. Extending this line of argument, Azar and I developed a simple model and estimated the present value (discounted to 1990 and expressed in 1990 USD) of the costs to stabilize atmospheric CO2 at 350 ppm, 450 ppm, and 550 ppm to be 18 trillion USD, 5 trillion USD, and 2 trillion USD respectively (see Azar & Schneider, 2002, which assumes a discount rate of 5% per year). Obviously, 18 trillion USD is a huge cost. The output of the global economy in 1990 amounted to about 20 trillion USD Note 6. Seen from this perspective, these estimates of the costs of abatement tend to create the impression that we would, as critics suggest, have to make draconian cuts in our material standards of living in order to reduce emissions and achieve the desired levels of CO2 concentration. These same critics view the cost estimates as unaffordable and politically impossible. However, viewed from another perspective, an entirely different analysis emerges. In the absence of emission abatement and without any damages from climate change, GDP is assumed to grow by a factor of ten or so over the next 100 years, which is a typical convention used in long-run modeling efforts. (The plausibility of these growth expectations is not debated here, but the following analysis will show how GDP is expected to grow with and without climate stabilization policies.) If the 350 ppm target were pursued, the costs associated with it would only amount to a delay of two to three years in achieving this aforementioned tenfold global GDP increase. Thus, meeting a stringent 350 ppm CO2 stabilization target would imply that global incomes would be ten times larger than today by April 2102 rather than 2100 (the date the tenfold increase would occur for the no-abatement-policies scenario). This trivial delay in achieving phenomenal GDP growth is replicated even in more pessimistic economic models. These models may be very conservative, given that most do not consider the ancillary environmental benefits of emission abatement (see the Figure below). Figure —Global income trajectories under business as usual (BAU) and in the case of stabilizing the atmosphere at 350 ppm, 450 ppm, and 550 ppm. Observe that we have assumed rather pessimistic estimates of the cost of atmospheric stabilization (average costs to the economy assumed here are $200/tC for 550 ppm target, $300/tC for 450 ppm, and $400/tC for 350 ppm) and that the environmental benefits in terms of climate change and reduction of local air pollution of meeting various stabilization targets have not been included. Source: Azar & Schneider (2002). Representing the costs of stringent climate stabilization as a few short years of delay in achieving a monumental increase in wealth should have a strong impact on how policymakers, industry leaders, and the general public perceive the climate policy debate. Similar results can be presented for the Kyoto Protocol: the drop in GDP below "baseline" levels that would occur if the Kyoto Protocol were implemented ranges between 0.05% and 1%, depending on the region considered and the model used (see IPCC WG III, chapter 8, and IPCC 2001c, p. 538). The drops in the growth rates for OECD countries over the next ten years would likely fall in the range of 0.005-0.1 percent per year below baseline scenario projections under the Kyoto Protocol. (It should be kept in mind that the uncertainties about baseline GDP growth projections are typically much larger than the presented cost-related deviations.) Furthermore, assuming a growth rate of 2 percent per year in the absence of carbon abatement policies, implementation of the Kyoto protocol would imply that the OECD countries would get 20 percent richer (on an annual basis) by June 2010 rather than in January 2010, assuming the high-cost abatement estimate. Whether that is a big cost or a small cost is of course a value judgment, but it is difficult to reconcile with the strident rhetoric of L.B. Lindsey (2001), President Bush's assistant on economic policy, who states on page 5 of his report that “the Kyoto Protocol could damage our collective prosperity and, in so doing, actually put our long-term environmental health at risk.” Some real-life and relatively short-term regional efforts at abating have demonstrated this idea. In Great Britain, for example, King, 2004 reports that between 1990 and 2000, the economy grew 30% and employment increased 4.8%, while at the same time, greenhouse gas emissions intensity fell 30% and overall emissions fell 12%. Many studies have reiterated the idea that many future GHG reduction measures will have little or no impact on local or international economies. One of the most well-known is Scenarios for a Clean Energy Future (CEF), which, as summarized by Brown et al. (2001), "concludes that policies exist that can significantly reduce oil dependence, air pollution, carbon emissions, and insufficiencies in energy production and end-use systems at essentially no net cost to the US economy." (For more summarization of CEF, see Gumerman et al. (2001)). Two other studies by the International Project for Sustainable Energy Paths (IPSEP), "Cutting Carbon Emissions at a Profit: Opportunities for the U.S." and "Cutting Carbon Emissions While Making Money", also concur. However, all this does not suggest that policies involving global emissions trading or carbon taxes would not be needed to achieve large cost reductions, nor does it mean that stabilizing CO2 below 500 ppm will be easy or will happen by itself. (See Hoffert et al (1998) for a sobering analysis of the departures from BAU needed to achieve such stabilization targets.) On the contrary, such a transition would require the adoption of strong policies, including such instruments as carbon taxes, tradable emission rights, regulations on energy efficiency, transfer payments to eliminate distributional inequities, enhanced R&D on new energy technologies, politically acceptable and cost-effective sequestration techniques, etc. There will be winners and losers, and difficult negotiations will be required within and across nations in order to devise cost-effective, fair burden-sharing of transition costs. If further debate leads to the consensus judgment that preventing “dangerous” anthropogenic climate change does indeed imply the need for stabilization of CO2 concentrations below 500 ppm, then it should no longer be possible to use conventional energy-economy models to dismiss the demand for deeply reduced carbon emissions on the basis that such reductions will not be compatible with overall economic development — let alone to defend strident claims that carbon policies will devastate the overall economy. Hopefully, a broader recognition that reduced CO2 emissions will at most only marginally affect economic growth rates by delaying overall economic expansion by a few years in a century will increase the acceptability of policies on climate change and will make politicians more willing to adopt much stricter abatement policies than are currently considered politically feasible. As of now, the policy stance on abatement is not particularly encouraging. Some major players in the climate debate – including the US, Australia, and Russia – are opposed to stringent emissions reduction on the grounds of economic arguments. Russia, for example, believes that becoming a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol will endanger the economic growth it has experienced in recent years, much of which has resulted from cheap energy and a significant increase in oil and gas production (see “Last chance for Kyoto”, Webster 2003). Nevertheless, in October 2004 Russia ratified the protocol, perhaps because of a side deal in which the European Union agreed to push for Russia's entry into the World Trade Organization. Conclusions - Implications for the Kyoto Protocol and BeyondResearch on the climate was performed mainly at a regional rather than international level through the end of World War II. After the war, there was increased demand for international cooperation in science, as evidenced by the 1947 World Meteorological Convention (see the International Cooperation section of Spencer Weart's website). Now, climate change is widely considered to be one of the most potentially serious environmental problems the world community will ever have to confront. This concern is what brought about additional cooperation in the form of the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which calls for stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations below “dangerous” levels, presumably through mitigation measures. However, the problem with mitigation is that climate services are essentially a public good, as stated by Perrings, 2003:

An international mitigation agreement therefore appears to be an excellent way in which to eliminate some of the problems associated with mitigation's nature as a public good. In a first step towards reaching this ultimate objective, the world's industrialized countries, except for the USA and Australia, have agreed to adopt near-term emission reduction targets as specified by the Kyoto Protocol. As mentioned above, Russia has finally ratified, pushing the agreement over the tipping point and it will go into effect. (In order for the Protocol to go into effect, at least 55 countries representing at least 55% of the developed world's 1990 carbon dioxide emissions must sign and ratify it. As of now, more than 55 countries have signed and ratified, but their cumulative emissions were well under 55%. Russia's signing and ratification pushed the treaty past the 55% mark.) Russia's CO2 emissions are likely already near 1990 levels, thanks mainly to rapid growth in its oil and gas industry, and the Protocol requires countries to reduce emissions to 5% below 1990 levels in the commitment period, which runs from 2008-2012. Some of the original appeal of the Kyoto Protocol for Russia was that it would have emissions credits to sell because after its economic collapse, its CO2 emissions were well below 1990 levels (so it would be able to sell emissions credits -- so-called "hot air" -- amounting to the difference between its emissions and 95% of 1990 emissions). Now that CO2 levels have risen, Russia appears to profit from the Kyoto Protocol in that way, which may explain its more recent internal debate with being signatory.However, as stated a promise to push for Russian entry into the WTO by the EU may have been the deal maker; see, for example, "EU welcomes Russia's Kyoto approval". Sadly, even Russia's leading scientists seem to have been pulled into the politics of climate change in that country. News reports have said that the Russian Academy of Sciences produced a document, which was given to President Putin, which was strongly opposed to Russia's ratification of the Kyoto Protocol, warning that the science behind the Protocol was weak, not to mention that signing it would halt economic development in Russia (see "Dragged into the fray"). Yuri Izrael, the lead author of the scientists' report, was accused of hypocrisy after its publication, as his anti-climate stance in the report contrasted starkly with the pro-climate outlook he took at meetings of the IPCC, an organization in which he is a vice-chairman. Fortunately, all of this is now history, and hopefully the contention will subside. The frustration characterizing the Kyoto proceedings proved, as Weart says, that "International diplomacy is a gradual process. The most important task is to shift attitudes step by step. Next comes the work, no less slow and difficult, of devising mechanisms to put decisions into practice, for example, ways to measure national emissions and processes to adjudicate quotas. The mechanisms might be hollow at the start but they could slowly become meaningful." Such frustrations are inherent in national-level policymaking attempts as well -- see Houck's, 2003 discussion of the "troubled marriage" between science and law in environmental policy. As the Kyoto Protocol shows, in the real world, climate policies are carried out under uncertainty about the climate system and the cost and possible rate of changes of the energy system. Therefore, hedging strategies are often proposed as the most reasonable policies (e.g., Lempert and Schlesinger, 2000). Given that climate change is generally considered likely to become a serious social and environmental problem, some early climate policies are prudent. The question is thus not whether something should be done at all, but rather what, how much, and who should pay. Optimization models have been used to analyze hedging strategies. We may designate a certain stabilization target and a year by which emissions must be under control, and then we can use a model to calculate the optimal near-term policies, taking into consideration uncertainty about the stabilization target. However, with such large degrees of uncertainty, it is next to impossible to arrive at any high-confidence conclusions. For that reason, energy-economy optimization models cannot help us to determine a single cost-efficient near-term policy. At best, they can produce a subjective probability distribution of possible “optimal” policies, depending on the probabilities of many assumptions used as variables in the model (see, e.g., Roughgarden and Schneider (1999)). At worst, they may come up with artificially low "optimal" levels of hedging/abatement due to the public good nature of mitigation, as discussed in Climate Damages and the Discount Rate. Given all the uncertainty about the climate and energy systems, real world climate policy implies that each generation will likely have to fight its own battle about how much to reduce its own emissions. The target will be constantly moving. Leaving emission abatements to future generations is the real world equivalent of avoiding an opportunity to reduce the emissions now without any guarantee of an increase in emission abatement in the future. Why would future generations be more inclined to reduce their emissions more if we reduce them less, or not at all? Note 7 It is in light of this analysis that the international process that produced the Kyoto Protocol should be viewed. The Kyoto Protocol requires that emissions from Annex I (i.e., developed) countries should be reduced by 5 percent below their 1990 levels by 2010, and although no targets have been negotiated for subsequent commitment periods, it is widely understood that Kyoto is but a first step towards more stringent targets. All three IPCC Assessment Reports have noted the need for cuts of 50% or more below most business as usual scenarios by the mid- to late- 21st century, and little or no emissions by the century's end to meet the goal of stabilizing atmospheric CO2 concentrations below a doubling of pre-industrial values. The IPCC's Third Assessment Report has clearly noted that eventually, all net carbon emissions must go to near zero to prevent the continuous buildup of CO2 concentrations in the 22nd century and beyond. Some analysts have assumed that the targets set by the Kyoto Protocol also apply for the next 100 years despite the fact that there is no support in the Protocol for such an interpretation (see Weyant (1999)). Comparisons of this fictitious “Kyoto forever” scenario were made with a case in which Kyoto was not enforced, but more reductions were carried out subsequently so that the climate implications by 2100 were essentially the same as those in the “Kyoto forever.” In this way, it was “proven” that “Kyoto forever” is not cost-efficient. Some have even argued that Kyoto (but essentially referring to “Kyoto forever”) is pointless because it could entail costs of hundreds of billions of dollars, with only marginal changes in global temperatures by 2100. In fact, they argue, the fictitious "Kyoto forever" protocol would delay the warming that would've occurred under a no-policies scenario by less than a decade. (See a quote from Lomborg's 2001 book, The Skeptical Environmentalist and the rebuttal of his “Kyoto forever” assumption by me in Scientific American. See also a report of the Danish Committees on Scientific Dishonesty regarding Lomborg's book, and a Reuters article, "Panel: Danish Environmentalist Work 'Unscientific'" pertaining to a similar report performed by a panel of Scandinavian scientists.) Members of the conservative movement have taken an even more aggressive stance, as discussed in McCright and Dunlap, 2000 and McCright and Dunlap, 2003. It is clear that these types of elliptical analyses have had an impact on U.S. politics, but they represent a fundamental misunderstanding of the idea behind Kyoto. The Protocol is meant to serve as the first step of an evolving process. More stringent policies can be expected, much in the same way the Montreal Protocol continuously sharpened reduction requirements on ozone-depleting substances as new scientific assessments proving the ozone hole was caused by human emissions of ozone-depleting substances became available. In addition, alternative energy must be improved, as it is nowhere near perfect. In fact, there has been much controversy over the efficiency and "greenness" of some sources (see "An ill wind?"). But the responsibility for doing this for climate change abatement lies with forthcoming political leaders and future generations. As noted, the IPCC has long made it clear that cuts of 50 percent and more below most baseline scenarios are needed in the 21st century to achieve even modest stabilization goals like 600 ppm and that fossil fuel emissions need to be phased out completely, as discussed below. Some countries and groups have already begun working towards much lower emissions levels. The government of the UK is calling for emissions levels to drop to 40% of 1990 levels by 2050, and says it is committed to reaching that goal (King, 2004). Many more examples can be found in Guidance on Uncertainties. The “Kyoto forever” scenario is essentially a massive climate change scenario that is a very small departure from the baseline scenarios that project a tripling or quadrupling of CO2 in 2100 and beyond (e.g., IPCC Synthesis Report, 2002 — Question 5, and in CO2 concentrations). However, it is unfair to assume that the first step towards emissions abatement (a Kyoto-like agreement) will be the only step for 100 years. Assuming that the Kyoto targets will remain as-is over the next 100 years, and then using that to shoot down the Kyoto protocol, which, in reality, has been negotiated to hold for only a decade, borders on intellectual dishonesty Note 8. No climate scientist has ever argued that adhering to “Kyoto forever” can bring about more than a marginal decrease in climate change to 2100 and beyond. But while “Kyoto forever” may be a cost-ineffective prescription, “no Kyoto” is a prescription to further delay the process of moving toward more stringent climate regimes that will very likely be needed in the decades ahead if stabilization concentrations below 600 ppm are to be achieved. To the disappointment of many world leaders, scientists, climate-conscious citizens, and others, the US is following the "no Kyoto" path for the foreseeable future. The Bush Administration refused to endorse the Kyoto Protocol in 2001, which had severely weakened the chances of it going into effect and made the US look careless and irresponsible on this serious issue, until Russia unexpectedly signed. How is it that a country responsible for 20% of the world's emissions, yet home to only 4% of the world's population, can avoid such an emissions treaty when it is one of the worst offenders? Those in favor of stringent climate policies will combat the argument that we should defer emission abatement and do more in the future by saying that we should do both. Those citing the arguments in the WRE paper for delayed abatement would say that the budget for emission abatement is limited, but the counterargument would be that although the budget is limited, arguments can also be made over how large it should be. Acting today is rather unlikely to imply that weaker climate policies will be carried out in the future. If low stabilization targets were so expensive to meet that it would not be possible to meet other worthy social and environmental obligations or objectives (e.g., clean water and energy systems, particularly in less developed countries), then it would be right to argue that higher targets should be accepted at the outset. One must concede that there are many other “worthy causes,” and for some of them, investments on their behalf would improve the problem and only produce a small delay in achieving large economic growth factors a century hence. But the climate problem is so laced with large uncertainties — including abrupt nonlinear events with catastrophic potential — and the possibility of many irreversible occurrences that a strong argument exists to consider climate change a compelling case for hedging actions above many other initiatives. Plus, as noted in IPCC (2001c), “ancillary benefits of climate policies can improve clean air and energy systems, helping to meet sustainable development objectives and climate stabilization goals simultaneously.” Thus, after assessing the benefits and costs of emission reduction and acknowledging the many uncertainties in every stage of the analysis — many of which have been emphasized here — it is a n easily defensible value judgment that the extra “climate safety” afforded by a few years of delay in income growth of a factor of five over 100 years is an insurance premium in planetary conservation well worth its price. Thus, although it is important that the global community act now to keep low stabilization targets (say, 400 ppm CO2) within reach, but as Azar and I argued, overshooting the long-run target for a few decades during the transition in order to control costs in the short run seems also to be a prudent step on the road to strict targets, if that's what it takes to get an agreement to do it. That low stabilization target will require early abatement policies, and many scientists have debated what such policies should entail. Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern (2003) have suggested approaching climate change policy by studying institutions that have successfully protected the global commons in the past (i.e. - the Montreal Protocol). This falls into their framework for effective "adaptive governance" on environmental issues, which entails not only the study of successful commons policies, but also gathering, using, and providing information; learning from past conflicts and applying that knowledge to potential future ones; inducing rule compliance; and providing physical, technological, and institutional infrastructure and capacity building. Aubrey Meyer of the Global Commons Institute has long argued in favor of the principle of "contraction and convergence", or C&C. "Contraction" entails the shrinking of the developed countries' "share" of greenhouse gas emissions (and therefore atmospheric concentrations of GHGs). In this view, rich countries, who, on a per capita basis, enjoy a disproportionate fraction of the atmospheric commons, as shown in the figure below, need to reduce their emissions, while at the same time allowing poorer countries to "catch up" by increasing their per capita emissions. The idea is that, once an appropriate level of atmoshperic GHGs has been set, each country will be allocated a portion of the worldwide carbon budget depending at first on the global distribution of income, and over time, each country's per capita emissions allowance will converge, and overall emissions worldwide will be lower than they were previously. This "convergence" implies greater equity in emissions across nations while at the same time emissions targets for the world as a whole are met — see "Trading Up to Climate Security" and a related slide show. Meyer welcomes an Ashton and Wang (2003) quote on the subject: "...any conceivable long-term solution to the climate problem will embody, at least in crude form, a high degree of contraction and convergence. Atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases cannot stabilize unless total emissions contract; and emissions cannot contract unless per capita emissions converge" (see also Beyond Kyoto: Advancing the International Effort Against Climate Change). C&C is gaining popularity internationally and was discussed in detail at the ninth Conference of the Parties (COP9) in Milan at the end of 2003 (see "Greenhouse gas 'plan B' gaining support"). Figure (above) —CO2 emissions - in different regions in 2000, per capita and population. (Source: Climate Change Challenge Report, Grubb 2004, Chart 5.) Figure (below) —Contraction and Convergence Model - As shown, cumulative global emissions would rise as covergence is achieved and then would shrink again under contraction. (Source: Global Commons Institute). As more is learned of the risks to social and natural systems and as political preferences become better developed and expressed, targets and policies can always be revisited and adjusted up or down as necessary (see Rolling Reassessment in “Mediarology”). What cannot necessarily be re-fashioned is a reversal of abrupt nonlinear climatic changes and other impacts that present analyses consider possible. Very large uncertainties allow for the possibility of at least some “dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system” at relatively low stabilization targets, like 500 ppm (see Mastrandrea and Schneider, 2004). Thus, near-term abatement and the consideration of policies and actions for moving toward low stabilization concentrations, with the rethinking of the political landscape as new information comes in, should not be abandoned on the basis of arguments based on most existing integrated assessment models, given the well-known limitations in the structural and value-laden assumptions in these very preliminary tools. It must not be ignored that what we do in the next century about emissions will have long-term effect. The figure CO2 concentration, temperature and sea level shows global CO2 emissions peaking in the next fifty years or so and then steadily declining. They reach a very low level after 2100, when the fossil fuel era essentially ends. Even in this optimistic scenario, CO2 will stabilize at a much higher concentration than it has reached today, and temperature will rise accordingly. It will take even longer for sea level rise from thermal expansion and the melting of ice to occur, but notice that it’s all linked to how we handle our emissions now and in the next five to ten decades. What we choose to do over this century is absolutely critical to the sustainability of the next millennium. That is an awesome responsibility for the next few generations to bear, and to face it with denial — to give preference to limited immediate interests and inaccurate analyses — will not leave a proud legacy. A genuine dialog is long overdue for examining the environmental and societal risk of climate change based on sound science, multiple metrics, and a broad array of interests, not just elliptical pronouncements from special interest groups and political ideologists who misrepresent the mainstream science and economics of climate change. We owe the people, plants, and animals of the future nothing less than an honest and open debate. My relevant literature:

Links to others:

For more climate information, see:

|