|

Click

on a Topic Below |

| Home » Overview |

|

|

|

|

| An Overview of the Climate Change Problem |

Stephen Schneider’s climatechange.net is a critical component of Steve’s legacy, and is an outreach tool about which Steve cared deeply. He saw this website as way to effectively speak to diverse groups who are crucial to countering the misinformation campaigns of special interests and ideologues as well as developing and implementing effective climate policies: the media, the community of disciplinary scientists, decision makers at local, state, national and international levels, the faith communities, celebrities committed to supporting change, and corporate executives in key industries as well as the public—informing all of us of the latest findings and the risks we face, and inspiring us to continue to learn more and take action. And just as important, Steve was profoundly dedicated to influencing, impacting, and developing the next generation of climate scientists and policy makers through his teaching and outreach, as his many students will attest. The words mentor and friend are used together by so many that one wonders how one person could have so much impact on so many lives. Steve hoped that this website would be useful to all interested in the interdisciplinary science of climate change. As he said, this site is a work in progress — an in-depth mini-book with links to related websites and relevant literature, placed in a context that was his view of the climate problem. We are currently updating climatechange.net with new and updated content in his words that he wanted to have posted as well as reflections by people he taught. Please explore and come back often as this dynamic site evolves.

Throughout human history, climate has both promoted and constrained human activity. In fact, humans only very recently have been able to substantially reduce the degree to which they are affected by climate variability, mainly through advances in technology and the development of more sophisticated infrastructure. For example, high-yield agriculture and efficient food distribution and storage systems have virtually eliminated famine in most countries with developed or transitioning economies. On the other hand, human activity can and has also affected the climate. From Swedish scientist Arrhenius' 1896 study of how changes in carbon dioxide (CO2) could affect climate, to English engineer G.S. Callendar's assertion in 1938 that a warming trend caused by increases in CO2 was underway, to Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientist Lorenz's suggestion at a 1965 conference in Boulder, CO, that climate change could cause catastrophic "surprises", to the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, support has increased for the idea that there exists a complex, and perhaps dangerous, society-nature cycle: climate influences human activities that, in turn, influence climate, etc. (For much more information on the history of climate change research, see Spencer Weart's website, The Discovery of Global Warming.) |

| "As the climate continues to change —and in most mainstream scientific studies, change is expected to accelerate substantially during the twenty-first century— we can expect natural systems to become highly stressed." |

However, climate change didn't jump onto the global public's radar screen, politicians, and the media as an important issue until 1995, when the IPCC first announced in Working Group I's contribution to the Second Assessment Report, or SAR (which was released in final form in 1996), that "the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on global climate." The record high temperatures in the last few decades (see a 2003 article in The Guardian), with 1998, 2002, and 2003 being the warmest years on record, as well as dramatic increases in storm damage between the 1960s and 1990s, have lent credibility to the IPCC’s finding (see a Trend Graph from the IPCC and a similar figure from page 4 of a presentation given by Ray Bradley; original Mann et al., 2003). Then, in its Third Assessment Report (TAR) in 2001, the IPCC estimated that by 2100, the planet would warm by between 1.4 °C and 5.8 °C, up from the range of 1.0 °C to 3.5 °C that had been estimated in the SAR. While warming at the low end of this range, of say 1.5 °C, would likely be relatively adaptable for most human activity, it would still be significant for some “unique and valuable systems.” Warming of 6 °C could have widespread catastrophic consequences, as a temperature change of 5 to 7 °C on a globally averaged basis is about the difference between an ice age and an interglacial period. The 2001 IPCC assessment both reinforced the original (1996) claim of detection of an anthropogenic climate signal and brought to the forefront a new “discernible” statement — this time that recent observations of wildlife, marine systems, ice layers, and the timing of vegetation lifecycles suggest that there now appears to be a discernible impact of regional climatic variations on natural systems (see IPCC Working Group II Report and Root/Schneider: Wildlife Responses to Climate Change: Implications). The prime implication of this new finding is that as the climate continues to change —and in most mainstream scientific studies, change is expected to accelerate substantially during the twenty-first century— we can expect natural systems to become highly stressed.

This website is divided into sections reflecting the four major components of the climate change debate: 'Mediarology', Climate Science, Climate Impacts, and Climate Policy. I will summarize all four below.

| "“End of the world” and “good for the Earth” are, in my experience, the two lowest probability cases." |

Special interest groups followed the IPCC proceedings closely. Given the broad range of possible outcomes, proponents of the many sides of the climate change debate (often dichotomized into “ ignore the problem ” versus “stop it ” camps, though it is actually an issue with many, many sides) deliberately selected and continue to select information out of context that best supports their ideological positions and their or their clients' interests. They frequently practice a phenomenon I call "courtroom epistemology": refusing to acknowledge that an issue (climate change, in this case) is multifaceted, and presenting only their own arguments, ignoring opposing views. Deep ecology groups point to the most pessimistic outcomes, using their warnings of climate catastrophe to push for the creation and implementation of energy taxes, abatement policies, and renewable energy promotion and subsidies (as many believe renewable energy is “the solution). Clearly, such policies would affect the industries that produce and use the most energy, especially the oil and auto industries. The auto, oil, and other fossil fuel-intensive industry groups, uncoincidentally, tend to be the extreme optimists in the global warming debate though, ironically, they often are the pessimists when it comes to estimating the costs of fixing the problem. They attempt to trivialize the potential hazards of climate change and focus on the least serious outcomes and the most expensive mitigation policies to discourage political action.

This plays into the media's tendency to engage in "balanced" reporting: polarizing an issue (despite its being multifaceted) and making each "side" equally credible. The media dutifully report the dueling positions of ecology and industry, further confusing policymakers and the public with an endless parade of op-eds and stories quoting those suggesting that global warming is either “good for the Earth and too expensive to fix anyway” or “the end of the world but nonetheless relatively cheap to solve with solar or wind power.” “End of the world” and “good for the Earth” are, in my experience, the two lowest probability cases (as are "it would bankrupt us to mitigate climate changes" and "technology will solve climate change at no cost"). Neither side usually offers probabilities of such outcomes.

| "Just because we scientists have Ph.D.s we should not hang up our citizenship at the door of a public meeting." |

Eliminating this confusion and misrepresentation of the climate change debate requires the participation of scientists, citizens, and journalists alike. First, scientists should not be discouraged on principle to enter the public debate on climate change both as scientist-advocates and scientist popularizers; if they don't, popularization of potential probabilities and consequences of climate change will occur without their input and will likely be more inaccurate. A scientist should also transcend prejudices against non-frequentist (i.e., subjective) analysis and treat climate change like the issue that it is: one for which future empirical data cannot be obtained (as it is simply impossible to obtain hard data for events occurring in the future) and which therefore necessitates the use of Bayesian, or subjective, probabilities and projections/models — our 'cloudy crystal balls' — that compile all the information we can possibly bring to bear on the problem, including, but not limited to, direct measurements and statistics. It is scientists, not policymakers, who should provide subjective probabilistic assessments of climate change. Just because we scientists have Ph.D.s we should not hang up our citizenship at the door of a public meeting — we too are entitled to advocate personal opinions, but we also have a special obligation to make our value judgments explicit. If they do express opinions, scientists should attempt to keep their value judgments out of the scientific assessment process but should make their personal values and prejudices clear regardless. It is then the role of the scientist-popularizer to propagate and promote these assessments and values in an understandable manner in the public realm so that the scientific community's findings and the scientist's ideas are heard and his/her suggestions are available. An effective scientist-popularizer must balance the need to be heard (good sound bites) with the responsibility to be honest (see "the double ethical bind pitfall") as well. Doing both is essential.

Citizens must demand that scientists provide honest, credible assessments that answer the "three questions of environmental literacy": 1) What can happen?; 2) What are the odds of it happening?; and 3) How are such estimates made? Citizens must also achieve a certain level of environmental, political, and scientific literacy themselves so that they feel comfortable distinguishing climate change fact from fiction and making critical value judgments and policy decisions, in essence becoming "citizen scientists". Just as popularization of potential probabilities and consequences will occur with or without input from scientists, policy decisions will be made with or without input from an informed citizenry. I hope that citizens will take responsibility for increasing their scientific, political, and environmental literacy and recognize the importance of the positive effect that an informed public will have on the policy process.

Citizens and scientists clearly can't operate as completely separate entities in the climate change debate. Their interaction is essential, especially when it comes to "rolling reassessment". Given the uncertain nature of climate change, citizens and scientists should work together to initiate flexible policies and management schemes that are revisited, say, every five years. The key word here is flexible. Knowledge is not static — there are always new outcomes to discover and old theories to rule out. New knowledge allows us to reevaluate theories and policy decisions and make adjustments to policies that are too stringent, too lax, or targeting the wrong cause or effect. Both scientist-advocates and citizen-scientists must see to it that once we’ve set up political establishments to carry out policy that people do not become so vested in a certain process or outcome that they become reluctant to make adjustments, either to the policies or the institutions.

| "Citizens should make sure that the public debates take into account all knowledge available on climate change." |

In addition, citizens and scientists must coordinate with journalists and other media figures to ensure accuracy in the media portrayal of climate change (see The Journalist-Scientist-Citizen Triangle). We scientists need to take more proactive roles in the public debate. We need to help journalists by agreeing to participate in the public climate change debate and by using clear metaphors and ordinary language once we do so. We should go out of our way to write review papers from time to time and to present talks that stress well-established principles at the outset of our meetings. Before we turn to more speculative, cutting-edge science; we should deliberately outline the consensus before revealing the contention. Citizens should make sure that the public debates take into account all knowledge available on climate change. Hopefully, their actions will encourage reporters to replace the knee-jerk model of "journalistic balance" with a more accurate and fairer doctrine of "perspective": one that communicates not only the range of opinion, but also the relative credibility of each opinion within the scientific community. (Fortunately, most sophisticated science and environment reporters have abandoned the journalistic tradition of polarization of only two "sides", but nevertheless, especially in the political arena, such falsely dichotomous "balance" still exists).

To further clarify the climate change issue, we must consider its three main components: Climate Science, Climate Impacts, and Climate Policy (see below).

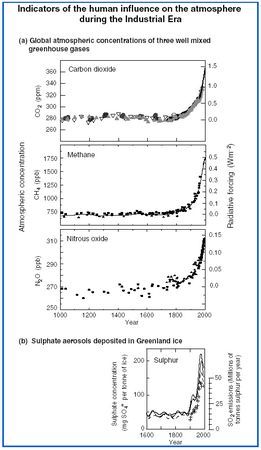

Figure — Indicators of human influence on the atmosphere since 1000 A.D. (source: IPCC, Working Group I, Summary for Policy Makers, figure 2).

The climate change debate is characterized by deep uncertainty, which results from factors such as lack of information, disagreement about what is known or even knowable, linguistic imprecision, statistical variation, measurement error, approximation, subjective judgment on the structure of the climate system, among others (see Decision Making Under Uncertainty). These problems are compounded by the global scale of climate change, which produces varying impacts at local scales, long time lags between forcing and its corresponding responses, very long-term climate variability that exceeds the length of most instrumental records, and the impossibility of before-the-fact experimental controls or empirical observations (i.e., there is no experimental or empirical observation set for the climate of, say, 2050 AD, meaning all our future inferences cannot be wholly “objective,” data-based assessments — at least not until 2050 rolls around). Moreover, climate change is not just a scientific topic but also a matter of public and political debate, and degrees of uncertainty and various claims and counterclaims may be played up or down (and further confused, whatever the case) by stakeholders in that debate (see Post-Normal Science).

| "In the past few centuries, atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased by more than 30 percent, and virtually all climatologists agree that the cause is human activity, predominantly the burning of fossil fuels and, to a considerable extent, land uses such as deforestation. " |

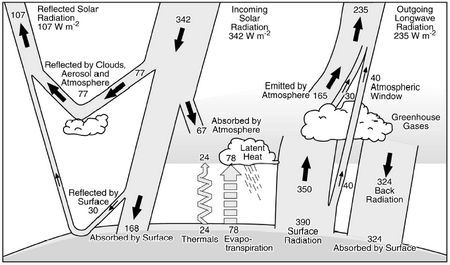

However, it is important to understand that the greenhouse phenomenon is well-understood and solidly grounded in basic science (see Climate Science). It is scientifically well-established that the Earth's surface air temperature has warmed significantly, by about 0.7°C since 1860, and that an upward trend can be clearly discerned by plotting historical temperatures. Such a graph would show a rapid rise in temperature at the end of the twentieth century. This is supported by the fact that all but three of the ten warmest years on record occurred during the 1990s. In addition, it is well-established that human activities have caused increases in radiative forcing, with radiative forcing defined as a change in the balance between radiation coming into and going out of the earth-atmosphere system. In the past few centuries, atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased by more than 30 percent, and virtually all climatologists agree that the cause is human activity, predominantly the burning of fossil fuels and, to a considerable extent, land uses such as deforestation.

More controversial is the extent to which humans have and are contributing to climate change. How much of global warming up to this point has been natural versus anthropogenically-induced, and by how much will humans and natural changes in the Earth each contribute to future disturbance? The IPCC has attempted to tackle this in its Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES), which contains a range of possible future emissions scenarios based on different assumptions regarding economic growth, technological developments, and population growth, arguably the three most critical determinants of future climate change. These have been used to project the increases in CO2 concentrations (and other radiative constituents) out to 2100, and it is hoped that they will help policymakers weigh action to stem potentially devastating consequences in the future. (For more information, see Scenarios).

These and other climate change projections depend on detailed modeling. The most consistent way scientists codify our knowledge is by constructing models made up of the many subcomponents of the climate system that reflect our best understanding of each subsystem. The system model as a whole cannot be directly verified before the fact — that is, before the future arrives — but it can be tested against historical situations that resemble aspects that we believe will occur in the future (see Climate Modeling). The most comprehensive models of atmospheric conditions are three-dimensional, time-dependent simulators known as general circulation models (GCMs) — see Climate Science. The most useful GCMs are those that also project "surprise" events, and are able to test emissions scenarios that can avoid such surprises.

While modeling has become both more complex and more accurate as computing abilities have advanced and more is understood about the climate problem, scientists still have to deal with an enormous amount of uncertainty, as mentioned above. In climate modeling, one major unknown is climate sensitivity, the amount by which the global mean temperature will increase for a doubling of CO2 concentrations. Many scientists have done extensive empirical and modeling research on this subject, and most have found that most climate sensitivity estimates fall somewhere within the IPCC's range of 1.5-4.5 °C. However, more recently some have estimated it could be lower than 1.5 °C or it could be an alarming 6 °C or higher (see Karl and Trenberth, 2003). (Remember that a 5-7 °C drop in temperature is all that separates Earth’s present climate from an ice age).

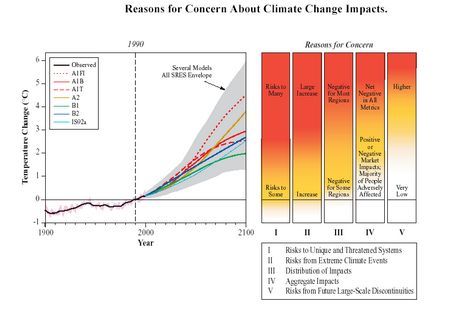

Figure — Reasons for concern about climate change impacts (source: IPCC WG 2 TAR, figure SPM-2). The left part of the figure displays the observed temperature increase up to 2000 and the range of projected increases after 2000 as estimated by IPCC, WG I (IPCC, 2001a) for scenarios from the Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES — see the Emission scenarios). The right panel displays conceptualizations of five reasons for concern regarding climate change risks evolving through 2100. White indicates neutral or small negative or positive impacts or risks, yellow indicates negative impacts for some systems, and red means negative impacts or risks that are more widespread or greater in magnitude. This figure shows that the most potentially dangerous impacts (the red colors on the figure) typically occur after a few degrees warming — thus, my later use of 3.5 °C as a tentative “threshold” for serious climate damages is very conservative. The risks of adverse impacts from climate change increase with the magnitude of climate change.

It is important that scientists continue to develop more credible models and probe the issue of climate sensitivity, as improvements in the science will lead to improvements in our understanding of the potential impacts of various levels of temperature change. Despite uncertainties surrounding sensitivity, the IPCC has projected that, if its latest estimate that on a global average basis, the Earth's atmosphere near the surface will warm somewhere between 1.4 and 5.8 °C by 2100 is correct, likely effects will include: more frequent heat waves (and less frequent cold spells); more intense storms (hurricanes, tropical cyclones, etc.) and a surge in weather-related damage; increased intensity of floods and droughts; warmer surface temperatures, especially at higher latitudes; more rapid spread of vector-borne disease; loss of farming productivity in warm climates and movement of farming to other regions, most at higher latitudes; rising sea levels, which could inundate coastal areas and small island nations; and species extinction and loss of biodiversity (see table - Projected effects of global warming). Schneider, Kuntz-Duriseti, and Azar (2000) have argued that the best way to estimate the full extent of such damages comes from examining not just quantifiable monetary ("market") damages, but several metrics, termed the "five numeraires": monetary loss (market category), loss of life, quality of life (including coercion to migrate, conflict over resources, cultural diversity, loss of cultural heritage sites, of hunting grounds, etc.), species or biodiversity loss, and distribution/equity. Use of multiple metrics should ensure a fairer, more comprehensive assessment of the actual benefits of avoiding global warming.

| "Policymakers are better able to determine what is 'dangerous' and formulate effective legislation to avoid such dangers if probabilities appear alongside scientists' projected consequences." |

Estimating climate damages that are expected to occur gradually and their effects is simple relative to forecasting "surprise" events and their consequences (see Climate Surprises). The IPCC and others have stated that "dangerous" climate change, including surprises, could occur, especially with more than a few degrees Celsius of additional warming. Surprises, better defined as imaginable abrupt events, could include deglaciation or the alteration of ocean currents (the most widely-used example of the latter being the collapse of the Thermohaline Circulation, or THC, system in the North Atlantic). Rather than being ignored, surprises and other irreversibilities like species extinctions should be treated like other climate change consequences by scientists performing risk assessments, where risk is defined as probability x consequence. The probability component of the risk equation will entail subjective judgment on the part of scientists, but this is far preferable to avoiding the risk equation entirely. Policymakers are better able to make a judgment about what is "dangerous" and formulate effective actions to avoid such dangers when probabilities appear alongside scientists' projected consequences.

These probabilities and consequences will vary regionally (see Regional Impacts). In general, temperature rises are projected to be greatest in the subpolar regions, and to affect the winter more dramatically than the summer. Hotter, poorer nations (i.e., developing nations near the equator) in the political "South" are expected to suffer more dramatic effects from climate change than their cooler developed neighbors in the political "North". This is partly due to the lower expected adaptive capacities of future societies in developing nations when compared with their developed-country counterparts, which in turn depend on their resource bases, infrastructures, and technological capabilities. This implies that impacts may be asymmetrically felt across the developed/developing country divide. The scenario in which climate change brings longer growing seasons to the rich northern countries and more intense droughts and floods to the poor tropical nations is clearly a situation ripe for increasing North-South tensions in the twenty-first century, especially since the economic benefits of using the atmosphere as a "dump" for our tailpipes is disproportionately in favor of the wealthy.

| "All people, governments, and countries should realize that 'we're in this together'." |

Regardless of the different levels of vulnerability and adaptive capacity that future societies are expected to have and the need for regional-level assessments, all people, governments, and countries should realize that "we're in this together". In all regions, people's actions today will have long-term consequences. Even if humanity completely abandons fossil fuel emissions in the 22nd century, essentially irreversible long-term concentration increases in CO2 are projected to remain for centuries or more. Thus, the surface climate will continue to warm from this greenhouse gas elevation, with a transient response of centuries before an equilibrium warmer climate is established. How large that equilibrium temperature increase is depends on both the final stabilization level of the CO2 and the climate sensitivity. One threat of a warmer climate would be an ongoing rise in sea level. Warmer atmospheric temperatures would lead to warmer ocean water (and corresponding volumetric expansion) as the heat becomes well-mixed throughout the oceans — a time known to be on the order of 1,000 years. Instead of only up to a meter of sea level rise over the next century or two from thermal expansion — and perhaps a meter or two more over the five or so centuries after that as the warming penetrates all depths of the ocean — significant global warming could very well trigger nonlinear events like a deglaciation of major ice sheets near the poles. That would cause many additional meters of rising seas for many millennia, and once started might not be reversible on the time scale of thousands of years (see figure - CO2 concentration, temperature and sea level). Thus, the behavior of only a few generations can affect the sustainability of coastal and island regions for a hundred generations to come.

| "The decision on whether to take actions on climate change entails a value judgment on the part of the policymaker regarding what constitutes "dangerous" climate change, ideally aided by risk assessments provided by scientists." |

In the face of such uncertainty, potential danger, and long-term effects of present actions, how should climate change policy be approached?

Climate change and almost all interesting socio-technical problems with strong stakeholder involvement fall into the post-normal science categorization: they are riddled with “deep uncertainties” in both probabilities and consequences that are not resolved today and may not be resolved to a high degree of confidence before we have to make decisions regarding how to deal with their implications. With imperfect, sometimes ambiguous, information on both the full range of climate change consequences and their associated probabilities, decision-makers must decide whether to adopt a "wait and see" policy approach or follow the "precautionary principle" and hedge against potentially dangerous changes in the global climate system. Since policymakers operate on limited budgets, they must determine how much to invest in climate protection versus other worthy improvement projects — e.g., new nature reserves, clean water infrastructure, or education.

Ultimately, the decision on whether to take actions on climate change entails a value judgment on the part of the policymaker regarding what constitutes "dangerous" climate change, ideally aided by risk assessments provided by scientists. These risk assessments can be enhanced by explanations of integrated assessment models (IAMs), which are important tools for studying the impacts of climate change on the environment and society (see Climate Impacts), as well as the costs and benefits of various policy options and decisions (see Climate Policy). As evidenced by interactions at international climate negotiations and the different degrees to which climate change abatement and/or adaptation policies have been adopted by different countries (see "Come On, Everybody Else Is Doing It"), not all policymakers' value judgments are equal.

| "The most robust policy strategies are often those which provide “ancillary benefits..." |

While a decision-maker must make the final decision on policy, many scientists have encouraged the "better safe than sorry" approach and have advocated the practice of hedging: initially slowing down our impacts on the climate and then adopting flexible policies that can be updated as future climate conditions occur and are better understood. As Christian Azar and I (Schneider and Azar, 2001) mentioned: "In our view, it is wise to keep many doors — analytically and from the policy perspective — open. This includes acting now so as to keep the possibility of meeting low stabilization targets open. As more is learned of costs and benefits in various numeraires and political preferences become well developed and expressed, interim targets and policies can always be revisited." In addition to being based on "rolling reassessment", as described in the quote above, the most robust policy strategies are often those which provide “ancillary benefits” — that is, policies which help to solve more than one problem at once. (See Climate Policy). For example, reducing the unfiltered burning of coal, which is highly polluting, in crowded cities like New Delhi and Beijing by replacing it with more efficient, less polluting natural gas power sources not only reduces the emissions of greenhouse gases that cause climate change, but also reduces the conventional “criteria” air pollutants that are well-known to adversely affect human health (see the EPA and Harvard School of Public Health websites on air pollution hazards to health).

Cost-benefit analyses (CBAs) are also useful in deciding the ifs and whats of climate change policy, but uncertainties make this exercise difficult as well, especially when attempting to estimate the costs of surprise and other catastrophic events. A few economists have concluded that stringent measures to control emissions of CO2 would be very costly even when the benefits of reducing the emissions (i.e., avoided climatic changes) are taken into account, but many others have found that much stronger cuts in emissions are defensible on economic efficiency grounds alone. At present, it seems that CBAs applied to the problem of global climate change can largely justify a wide range of emission reduction targets, marginal or substantial. The latter will be particularly justifiable if nasty surprises are taken into account.

| "Encouraging technological change through energy policies in particular is of critical importance when addressing climate change." |

Any policies that are implemented should provide incentives for, and possibly even go so far as to subsidize, technological change. Encouraging technological change through energy policies in particular is of critical importance when addressing climate change. For example, rapid early growth in alternative energy sources like wind and photovoltaic (PV) technology largely depends on government efforts to build these markets through subsidies. If/when the government supports such initiatives, they gain mainstream popularity and encourage further private investments, oftentimes above and beyond what the policy provides. On the other hand, if policy measures are delayed, public acceptance will likely be delayed as well. If the world decided to defer implementation of the Kyoto Protocol for another twenty years, for instance, it is likely that private and government research, development, and demonstration of carbon-efficient technologies would drop rather than increase. An overview of the climate-energy-policy debate (including a summary and critique of the Bush climate response) can be found in Holdren 2003 (see also "Report by the E.P.A. Leaves Out Data on Climate Change" and "The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: Does the Bush Administration Think It Can Fool Mother Nature?").

Future international climate change agreements should certainly consider the contributions of the developed (high per capita emissions) versus developing (low per capita emissions) countries to climate change. Aubrey Meyer of the Global Commons Institute has long argued for the principle of "contraction and convergence." "Contraction" entails the shrinking of the developed countries' "share" of CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions. In Meyer's view, rich countries, who are appropriating a disproportionate fraction of the atmospheric commons, need to cut back their emissions and allow poorer countries to emit more and catch up. Eventually, the two groups will "converge" at a level at which per capita emissions will be equal across nations while at the same time meeting "climate safe" emissions targets for the world as a whole (see "Trading Up to Climate Security").

| "Substantial reductions of carbon emissions and several fold increases in economic welfare are compatible targets." |

For all countries, a main factor influencing implementation of climate policy today is based on a clarification of the overall costs of stabilizing atmospheric CO2 levels (see Political Feasibility). More pessimistic economists generally find deep reductions in carbon emissions to be very costly — into the trillions of dollars. For instance, stabilizing CO2 in 2100 at 450 ppm (current level is about 360 ppm) would, according to Manne & Richels (1997), cost the world between 4 and 14 trillion USD (this is the present value for the whole century). Other top-down studies report similar cost estimates (see IPCC 2001c, chapter 8), but we must note, paradoxically, that the results of even the most pessimistic economic models support the conclusion that substantial reductions of carbon emissions and several fold increases in economic welfare are compatible targets. To support this, Christian Azar and I developed a simple economic model and estimated the present value (discounted to 1990 and expressed in 1990 USD) of the costs to stabilize atmospheric CO2 at 350 ppm, 450 ppm, and 550 ppm to be 18 trillion USD, 5 trillion USD, and 2 trillion USD, respectively, assuming a discount rate of 5% per year (see Azar & Schneider, 2002). Obviously, 18 trillion USD is a huge cost, considering that the output of the global economy in 1990 amounted to about 20 trillion USD and is about 37 trillion in 2003. However, viewed from another perspective, an entirely different analysis emerges: the 18 trillion USD cost represents the present value of lost income over the next 100 years. In the absence of emission abatement and without any damages from climate change, GDP is assumed to grow by a factor of ten or so over the next 100 years, which is a typical value used in long-run modeling efforts. If even the most stringent target, 350 ppm, were pursued, the costs associated with it would only amount to a delay of two to three years in achieving this tenfold increase in global GDP in 2100. Meeting the 350 ppm CO2 stabilization target would imply that global income would be ten times larger than today by April 2102 rather than 2100 (the date at which the tenfold increase would occur for the no-abatement-policies scenario). This trivial delay in achieving phenomenal GDP growth is replicated even in more pessimistic economic models. These models may be very conservative, given that most do not consider the ancillary environmental benefits of emission abatement, among other shortcomings.

Further Information

Throughout this website, I will try to distinguish the well-established components of the climate change debate, contrast them with the speculative aspects (and the overly contentious media/political debate), and ultimately put this problem in the context of so-called Integrated Assessment (see Integrated Assessment) of policy responses to the advent or prospect of global warming. I will also provide hundreds of links to other websites and literature that elaborate on various aspects of each of the many components of the debate, and will be sure that most points of view — some diametrically opposed to mine— are all represented. I will, of course, provide my own views on discordant opinions and their contexts that seem at variance with the increasingly concerned mainstream assessments that have emerged in the past decade (see “Mediarology”). The critical role of uncertainty will be frequently highlighted. (See, e.g., “When Doubt is a Sure Thing”, the Moss-Schneider Guidance Paper and a Climatic Change editorial on uncertainties). Finally, I suggest areas for further consideration.

For more detailed Climate Change information, see the full sections on:

For audio/video discussions of climate change:

-

Historical Schneider presentations are to be posted in new few weeks, so check back often. Right now, please go to Steve-In–Action for other great presentations.

For recent Climate Change news, see: News

- The Guardian Climate Change Reports

- SafeClimate News

- Environment Canada

- Grist Magazine Heat Beat

- U.S. EPA Global Warming — News and Events

- Climate Ark

Glossaries of Climate Change: