|

Click on a Topic Below |

| Home » Climate Science » ClimateScienceProjections |

| |

| |

| Climate Science Projections |

|

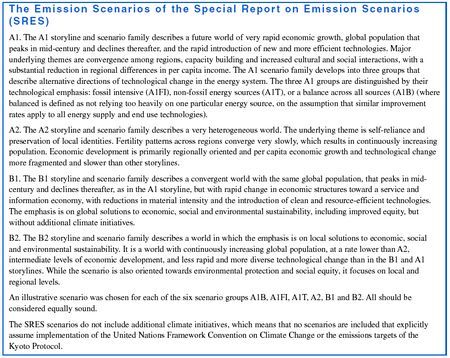

Using Scenarios to Develop a Plausible Range of Outcomes The IPCC commissioned the Special Report on Emission Scenarios to broaden assessments to include a range of outcomes and to focus analysis on a coherent set of scenarios to facilitate comparison. The scenarios produced by the SRES team rest on assumptions regarding economic growth, technological developments, and population growth, which are arguably the three most critical variables affecting the uncertainty over future climate change and policy options. To the extent possible, the IPCC's Third Assessment Reports (TARs) have referred to the SRES to inform and guide assessment. The box called Emission Scenarios, below, describes the baseline SRES scenarios; the figure previously shown, Variations of the Earth's surface temperature, demonstrates how the SRES scenarios have been used to evaluate projected temperature changes. Note: Very recently, two retired statisticians criticized the SRES scenarios as being extremely exaggerated (see Castles and Henderson, and an overview of their criticism of the SRES containing various letters and articles, and “Hot Potato” and “Hot Potato Revisited" — in the latter the Economist continues its error-filed critiques of climate issues, saying that the Lavoisier group that supported Castles is "an Autralian governmental body, whereas it is in fact a conservative dot com think thank notorious for contrarian rhetoric. It seems that from Lomborg to Casteles, the Economist just can't get it straight). Several economists and technologists have responded, showing that the purported criticisms of method cause only minor alterations to the original SRES results — see “IPCC SRES Revisited: A Response” by Nakicenovic et al., and a Manne-Richels working paper; also see "PPP-correction of the IPCC emission scenarios - does it matter?". In a January 2003 speech to the IPCC Task Group on Scenarios for Climate Impact Assessment (TGCIA), even Henderson admits that the emissions scenarios in the SRES are not totally inaccurate: "Should the scenario exercise be rethought? Yes, chiefly for the reasons that we have given but also for some others that we could have developed had time permitted. But does a radical revision need to be put in place, or attempted, specifically for the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4)? I think the answer to that second question is "No." Box — Emission scenarios of the Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES) (source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change SRES).

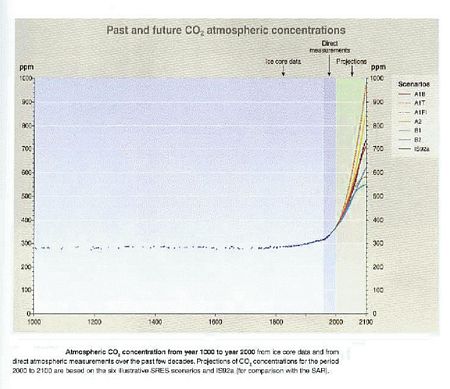

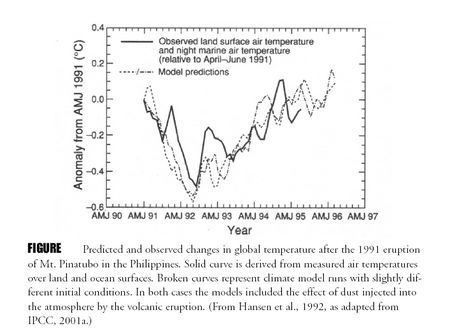

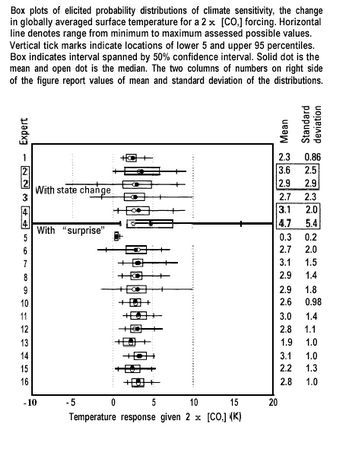

One of the most interesting contrasts across the SRES scenarios is that between the emission pathways of two variants of the A1 scenario family. The A1 family assumes relatively high economic growth, low population growth, and considerable contraction in income differences across regions — a world that builds on current economic globalization patterns and rapid income growth in the developing world. One variant of it, A1FI, is the fossil fuel intensive scenario, in which the bulk of energy needed to fuel economic growth continues to be derived from burning fossil fuels, especially coal. This results in the most CO2-heavy scenario: emissions grow from the current level of about 8 billion tons carbon per year to nearly 30, resulting in a tripling of CO2 (from current levels) in the atmosphere by 2100, and implying at least a quadrupling of CO2 as the 22nd century progresses. The contrasting variant is A1T — the technological innovation scenario — in which fossil fuel emissions increase from the present by about a factor of two until the mid-21st century, but then because of technological innovation and deployment of low carbon-emitting technologies, global emissions drop to well below current emissions by 2100. Even so, as seen in the figure, CO2 concentrations, below, CO2 levels roughly double by 2100. However, they do not increase much more in the 22nd century because emissions rapidly approach zero by 2100. Note that for all scenarios, despite their major differences in emissions, the CO2 concentrations projected are relatively similar for several decades, and their paths do not diverge dramatically until after the mid-21st century. This has led some to argue that since climate change will be relatively indifferent to these radically different scenarios in the next few decades, we should not work too hard to achieve rapid emissions cuts (i.e., we should spend very little on emissions abatement). The counter argument is that it takes many decades to replace energy supply and end use systems, thus delaying abatement for decades even if we start today. This explains why A1FI and A1T do not diverge until well into the 21st century. However, after the mid-21st century, there is a very large difference in cumulative emissions and their effects, which is important since they determine the eventual stabilization level of CO2 — and thus the eventual temperature increase — that will take place in the latter half of the 21st century and beyond. Figure — Past and future CO2 concentrations (source: IPCC, Working Group I, Summary for Policy Makers, figure 10a). Since most impact assessments (see Climate Impacts) suggest that the risk of very large damages from climate change occur for warming beyond a few degrees Celsius (see the Working Group II SPM), proponents of environmental sustainability strongly advocate keeping CO2 levels well below double the current level, perhaps stabilizing at no more than 450 parts per million (ppm). We are about 370 ppm now, a 30% increase over pre-industrial concentrations (see Schneider and Azar, 2001). Stabilization at 450ppm would require greater abatement efforts than is assumed in any of the SRES emission pathways, and thus is often opposed by economic growth advocates as “too expensive.” This argument has been challenged by Azar and Schneider, who show that very strict stabilization targets (like 450ppm or below) might only delay economic growth by a few years over an entire century, and thus the implementation of this “insurance premium” against the risk of dangerous climate change would hardly be noticed against the background of rapid and continuing economic growth that is assumed in scenarios like the A1 family laid out by the IPCC (see their Ecological Economics paper). Others (see Hoffert et al., 1998) have argued that achieving such low stabilization targets will require major efforts at technological innovation, and they advocate that it should begin now and accelerate over the next few decades. Who pays and how much it will cost will be a dominant subject of debate for climate policy analysts over the next ten years. (See Climate Policy). Climate Change Phenomena that Must be Considered in ForecastingThe SRES scenarios given in the Emission scenarios Box shown previously contain a possible future set of paths of plausible radiative forcings that are used to drive models of climate that make projections of possible climatic changes. Before showing the results of such projections, first a review of how the models are forced and how they work will be presented. Greenhouse Gases and Radiative Forcing. Although carbon dioxide is the most important of the anthropogenic greenhouse gases in terms of its direct effects on climate, other gases play a significant role, too (see the figures Global mean radiative forcing and Models of Earth's temperature). On a molecule-to-molecule level, most other greenhouse gases (except water vapor) are far more potent absorbers of infrared radiation than carbon dioxide is, but they are released in much lesser quantities and most persist for less time in the atmosphere, and so their overall effect on climate is smaller than that of CO2. Climatologists characterize the effect of a given atmospheric constituent by its radiative forcing, a term that describes the rate at which it alters absorbed solar or outgoing infrared energy. Currently, anthropogenic CO2, for example, produces a radiative forcing estimated at about 1.5 watts for every square meter (W/m2) of Earth's surface. (All forcings cited in this section are from the IPCC Third Assessment Report, Working Group I, Summary for Policymakers.) Recall that the solar energy absorbed by Earth and its atmosphere is about 235 W/m2 (see Details of Earth's energy balance), so the CO2 forcing is a relatively modest disturbance to the overall energy balance. Very crudely, one can think of 1.5 W/m2 of CO2 forcing (see Global mean radiative forcing) as having roughly the same effect as would an increase in the incoming sunlight energy by a little over 0.5% — an average of 1.5 watts on every square meter of the Earth's surface. The global warming resulting from a specified amount of radiative forcing after the climate has settled into a new equilibrium state is termed the climate sensitivity. If we knew the climate sensitivity and the concentration of all atmospheric constituents that affect radiative forcing, then we could more accurately predict future global warming. Climate sensitivity has been estimated by the IPCC to lie in the range of 1.5 to 4.5 oC of global average surface temperature warming for a doubling of CO2 concentrations over pre-industrial levels. Recent results, as we will see shortly, suggest the actual range of sensitivity is much broader than that; current knowledge cannot rule out fairly small sensitivities — around 1 oC — or very large ones — around 7 oC. First among the anthropogenic greenhouse gases after carbon dioxide is methane (CH4), which is produced naturally and anthropogenically when organic matter decays anaerobically (that is, in the absence of oxygen). Such anaerobic decay occurs in swamps, landfills, rice paddies, land submerged by hydroelectric dams, the guts of termites, and the stomachs of ruminants like cattle. Methane is also released from oil and gas drilling, from coal mining, from volcanoes, and by the warming of methane-containing compounds on the ocean floor. One methane molecule is roughly 30 times more effective at blocking infrared than is one CO2 molecule, although this comparison varies with the timescale involved and the presence of other pollutants. However, while CO2 concentration increases tend to persist in the atmosphere for centuries or longer, the more chemically-active methane typically disappears in decades — lowering its warming potential relative to CO2 on longer timescales. Currently, methane accounts for about one half a watt per square meter of anthropogenic radiative forcing, about one-third that of CO2. Other anthropogenic greenhouse gases include nitrous oxide, produced from agricultural fertilizer and industrial processes; and the halocarbons used in refrigeration. (A particular class of halocarbons — the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — is also the leading cause of stratospheric ozone depletion. Newer halocarbons that are replacing the CFCs in response to international treaties to ban ozone-depleting substances — see the Montreal Protocol — do not cause severe ozone depletion but are still potent greenhouse gases.) Together, nitrous oxide and halocarbons account for roughly another 0.5 W/m2 of radiative forcing. A number of other trace gases contribute roughly 0.05 W/m2 of additional forcing. All the gases mentioned so far are well-mixed, meaning they last long enough to be distributed in roughly even concentrations throughout the first 10 kilometers or so of the atmosphere. Another greenhouse gas is ozone (O3). Ozone occurring naturally in the stratosphere (some 10 to 50 kilometers above the surface) absorbs incoming ultraviolet radiation and protects life from UV-induced cancer and genetic mutations, hence the concern about anthropogenic chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) depleting the ozone layer and causing polar “ozone holes.” Unfortunately, ozone depletion and global warming have become confused in the public mind, even among political leaders and some environmental policy makers. The two are very distinct problems, and it's important to be very clear about this. The ozone-depletion problem is not the global warming problem! Ozone depletion is slowly coming under control thanks to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement that bans the production of the chlorinated fluorocarbons that destroy stratospheric ozone (see, e.g., the EPA ozone website or the NOAA ozone website). Whether similar agreements can be forged for climate-disturbing substances is part of what the current climate debate is about. Because ozone is a greenhouse gas, there are some direct links between greenhouse warming and anthropogenic changes in atmospheric ozone. Ozone in the lower atmosphere — the troposphere — is a potent component of photochemical smog, resulting largely from motor vehicle emissions. Tropospheric ozone contributes roughly 0.35 watt per square meter of radiative forcing, but unlike the well-mixed gases, it tends to be localized where industrialized society is concentrated. In the stratosphere, the situation is reversed. There, the anthropogenic effect has been ozone depletion, resulting in a negative forcing of approximately 0.15 W/m2. Thus, stratospheric ozone depletion would, on its own, cause a slight global cooling. Taken in the context of the more substantial positive forcings of other gases, though, the effect of stratospheric ozone depletion is a slight moderation of global warming — a moderation that will diminish as the ozone layer gradually recovers following the Montreal Protocol's ban on chlorofluorocarbons. The net effect of all anthropogenic ozone (both tropospheric and stratospheric) probably amounts to a slight positive forcing. The net forcing to date from all anthropogenic gases is probably around 3 W/m2, and is slated to become much larger if “business as usual” development scenarios are followed throughout the twenty-first century. Aerosols. The combustion of fuels, and, to a lesser extent, agricultural and industrial processes, produce not only gases but also particulate matter. Coal-fired power plants burning high-sulfur coal, especially, emit gases that photochemically transform in the atmosphere into so-called sulfate aerosols, whose high reflectivity turns back incoming solar radiation and thus results in a cooling trend. Natural aerosols from volcanic eruptions and the evaporation of seawater also produce a cooling effect. However, diesel engines and some burning of biomass produce black aerosols like soot, and these can warm the climate. Recent controversial estimates suggest that these could offset much of the cooling from sulfate aerosols, especially in polluted parts of the subtropics (see Jacobson, and Hansen et al.). The IPCC very roughly estimates the total radiative forcing resulting directly from all anthropogenic aerosols at -1 W/m2 (see Global mean radiative forcing). However, this figure is much less certain than the radiative forcings estimated for the greenhouse gases. Furthermore, aerosol particles also exert an indirect effect in that they act as “seeds” for the condensation of water droplets to form clouds. Thus, the presence of aerosols affects the color, size, and number of cloud droplets. An increase in sunlight reflected by these aerosol-altered clouds may result in as much as an additional -2 W/m2 of radiative forcing — again, with the minus sign indicating a cooling effect. Similarly, soot particles mixed into clouds can make the droplets absorb more sunlight, producing some warming. Taken together, aerosols add at least a watt per square meter of uncertainty into anthropogenic radiative forcing and complicate attempts to distinguish a true anthropogenic signal of climatic change from the noise of natural climatic fluctuations. Solar Variability. The sun's energy output varies, and this variation affects Earth's climate. Variations due to the 22-year solar activity cycle amount to only about one-tenth of one percent and are too small and occur too rapidly to have a discernible climatic effect. Long-term solar variations, either from variability of the Sun itself or from changes in Earth's orbit and inclination, could affect Earth's climate substantially and certainly have done so over geologic time. Satellite-based measurements of solar output, while accurate, are available for only a few decades. Despite this, climatologists can use indirect evidence of solar activity to estimate variations in solar energy output far into the past (see Hoyt and Schatten, 1997 for a detailed look at possible solar influences on climate). Such evidence suggests that solar forcing since pre-industrial times amounts to about 0.3 W/m2 — enough to contribute somewhat to the observed global warming but far below what is needed to account for all of the warming of recent decades. However, there is some speculation (see Baliunas) that magnetic disturbances from the Sun can influence the flux of energetic particles impinging on Earth's atmosphere, which in turn affect stratospheric chemical processes or even low clouds and might indirectly alter the global energy balance. These speculations have led some to declare the warming of the past century to be wholly natural, but this is discounted by nearly all climatologists because there is no demonstration or data showing that solar energetic particles can have such a large effect (see Global mean radiative forcing). In addition, it is unlikely that such solar magnetic events happened only in the past few decades and not at any other time over the past 1,000 years (see Variations of the Earth's surface temperature). Moreover, recent analyses point to major errors in past analyses of the sun's role (see Laut, 2003; and Kristjansson, Staple, and Kristiansen, 2002). But in the political world, citation of scientific evidence by advocates of a solar explanation for recent climate change often gets equal credibility until assessment groups like the IPCC are convened to sort out such claims and to weigh their relative probabilities. (For more information, see Contrarians and "Mediarology", and a NASA report) Net Radiative Forcing. The figure previously shown, Global mean radiative forcing, summarizes our best understanding (ca. 2000) of radiative forcings due to greenhouse gases, aerosols, land-use changes, solar variability, and other effects since the start of the industrial era. At the high ends of their ranges, the negative forcings (cooling) from some of these anthropogenic changes might appear sufficient to offset much of the warming due to anthropogenic greenhouse gases. This implication is misleading, however, because the effects of aerosols are short-lived and geographically localized compared with the long-term, global effects of the well-mixed greenhouse gases. Thus, we could achieve a rapid change in anthropogenic forcing (meaning more warming) if policies to reduce these short-lived emissions were implemented (see a Hansen Climatic Change Editorial, a Weubbles Editorial, and Human Forcing of Climate Change by Ralph Cicerone). The most advanced climate models, to be discussed shortly, are driven by a range of plausible assumptions for future emissions of all types, and they make it clear that the overall net effect of human activity is almost certainly a positive forcing at a global scale, but there could be significant departures at regional scales. More recently, Pielke, Sr. et al. have argued that landscape changes can also result in important forcings, at least at the regional scale and on century time scales (see "Is land use causing the observed climate trends?") . Feedback Effects. Knowing the radiative forcing caused by changes in atmospheric constituents would be sufficient to project future climate if the direct change in energy balance was the only process affecting climate. But a change in climate due to simple forcing can have significant effects on atmospheric, geological, oceanographic, biological, chemical, and even social processes. These effects can, in turn, further alter the climate, introducing yet another uncertainty into climate modeling. If that further alteration is in the same direction as its initial cause, then the effect is termed a positive feedback (see recent research by Jones et al. (2003) and Cox et al. (2000), both of the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research). If the further alteration counters the initial change, then it is a negative feedback. There are numerous different feedback effects, all of which greatly complicate the climate change issue. Here, we list just a few feedback effects, to give a sense of their variety and complexity. Ice-albedo feedback is an obvious and important feedback mechanism. Albedo describes a planet's reflectance of incident sunlight. Details of Earth's energy balance showed that Earth's albedo is about 0.31, meaning that 31 percent of incident sunlight is reflected back to space. A decrease in that number would mean Earth absorbed more sunlight, and global temperature would increase correspondingly. Now, suppose an anthropogenic increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide results in a temperature rise. One possible consequence is the melting of some ice and snow, which eliminates a highly reflective surface and exposes the darker land or water that lies beneath the ice. The result is a decreased albedo, increased solar energy absorption, and additional heating of Earth's surface. This is a positive feedback. Rising temperature also results in increased evaporation of water from the oceans. That means there is more water vapor in the atmosphere. Because water vapor itself is a greenhouse gas, increased concentration in the air results in still more warming and is thus another positive feedback. But increased water vapor in the atmosphere could also mean more widespread cloudiness. Clouds absorb outgoing infrared, resulting in a warming — another positive feedback. But, on the other hand, because clouds reflect sunlight, increased cloud cover would raise Earth's albedo, and less energy would be absorbed by the Earth-atmosphere system. This is a negative feedback, which counters the initial warming. There are actually a number of processes associated with clouds, some of which produce warming and some cooling, and they vary with the type of cloud, the location, and the season. Our still-limited understanding of cloud feedback effects is, in fact, one of the greatest sources of uncertainty surrounding global climate sensitivity — and thus climate projections. However, the best estimates suggest that the overall effect of increased water vapor is a positive feedback that causes temperatures to increase 50 percent higher than they would in the absence of this feedback mechanism (see, e.g., the Danny Harvey website and his books, Climate and Global Environmental Change and Global Warming: The Hard Science). Some feedbacks are biological. For example, increased atmospheric CO2 stimulates plant growth. More plants means more CO2 is removed from the atmosphere. This, then, is a negative feedback. But warmer soil temperatures stimulate microbial action that releases CO2 — a positive feedback effect. Drought and desertification resulting from climate change can alter the albedo of the land, replacing relatively dark plant growth with lighter soil and sand. Greater reflection of sunlight results in cooling and is a negative feedback. But here, as so often with the climate system, the situation is even more complex. If sand is wet, as on a beach, then it is darker, and therefore absorbs more sunlight than dry sand, yet dry sand is hotter. The resolution of this conundrum is that the wet sand is cooler because of the effects of evaporation, but the Earth is warmed by the wet sand since the evaporated water condenses in clouds elsewhere and puts the heat back into the overall system. Thus, cooling and warming of the Earth-atmosphere system does not always imply cooling or warming of the Earth's surface at that location. The removal of forests over the past few decades probably resulted in an increase in albedo — cooling the planet on average — but not necessarily cooling the local surface temperature. Feedbacks can be a very complicated business, and thus lead to a contentious, confusing, and sometimes inaccurate media debate (see “Mediarology”). There are even social feedbacks. For example, rising temperature causes more people to install air conditioners. The resulting increase in electrical consumption means more fossil-fuel-generated atmospheric CO2 — giving a small positive feedback. Treatment of all significant feedback effects is a tricky business, requiring not only identification of important feedback mechanisms but also a quantitative understanding of how those mechanisms work. That understanding often requires research at the outer limits of disciplines such as atmospheric chemistry and oceanography, biology and geology, and even economics and sociology. With positive feedback, some climatologists have speculated that there is a danger of “runaway” warming, whereby a modest initial warming triggers a positive feedback that results in additional warming. That, in turn, may increase the warming still further, and the process might continue until a very large temperature change has occurred. That, in fact, is what has happened on Venus, where the thick, CO2-rich atmosphere produced a “runaway” greenhouse effect that gives Venus its abnormally high surface temperature. Fortunately, it is highly likely in my view that the conceivable terrestrial feedbacks are, at least under Earth's current conditions, incapable of such dramatic effects. But that only means we aren't going to boil the oceans away; it doesn't preclude potentially disruptive climatic change. A climate model is a set of mathematical statements describing physical, biological, and chemical processes that determine climate. The ideal model would include all processes known to have climatological significance, and would involve fine enough spatial and temporal scales to resolve phenomena occurring over limited geographical regions and relatively short timespans. Today's most comprehensive models strive to reach this ideal but still entail many compromises and approximations. Often, less detailed models suffice; in general, climate modeling involves comparisons among models with different levels of detail and sophistication and, of course, with observed data. Computers are necessary to solve all but the simplest models. What must go into a climate model depends on what one wants to learn from it. A few relatively simple equations can give a decent estimate of the average global warming that is likely to result from a specified level of greenhouse forcings, but most models are much more complex than that. If we seek to model the long-term sequence of ice ages and interglacial warm periods, our model needs to include explicitly the effects of all the important components of the climate system that act over timescales of a million years or so. These include the atmosphere, oceans, the cryosphere (sea ice and glaciers), land surface and its changing biota, and long term biogeochemical cycles, as well as forcings from differing solar input associated with long-term variations in Earth's orbit and changes in the Sun itself. If we want to project climate over the next century, many of these processes can be left out of our model. On the other hand, if we want to explore climate change on a regional basis, or plan to look at variations in climatic change from day to night, then we need models with more geographic and temporal detail than a million-year global climate projection would have. Limits to Predictability? It is often asserted that meteorologists' inability to predict weather accurately beyond about five to ten days dooms any attempt at long-range climate projection (see a strong assertion of Robinson and Robinson in a widely disseminated op-ed piece opposing the Kyoto Protocol in the Wall Street Journal). That misconception ignores the differences of scale (particularly time scale) stressed in the preceding paragraph. In fact, it is impossible, even in principle, to predict credibly the small-scale or short-term details of local weather beyond about ten days — and no amount of computing power or model sophistication or weather monitoring systems is going to change that. This is because the state of the atmosphere is an inherently chaotic system, in which the slightest perturbation here today can make a huge difference in the weather a thousand miles away a month later. That does not mean that better weather-observing systems (or better weather models themselves) wouldn't improve the accuracy of weather forecasts over the ten or so day “predictability period” (after which chaotic dynamics degrade any forecast). But unlike weather, large-scale climate — climate being a long-term average of weather — changes are not primarily random, at least not on decadal to century time scales. Appropriate models can therefore make reasonable climate projections decades or even centuries forward in time — provided, of course, that we have credible emissions scenarios or solar forcings to provide “boundary conditions” to drive the models. The support for this assertion is that every year, winter is about 15 oC (plus or minus a degree or so) colder than summer in the Northern Hemisphere and about 5 oC colder than summer in the more ocean-dominated Southern Hemisphere, both of which are direct responses to the 100 W/m2 of radiative forcing from the Earth's seasonal orbital geometry relative to the sun. The plus or minus one degree is the chaotic dynamics part related to weather unpredictability. Thus, weather forecasting — known as an “initial value problem” — butts into the predictability limits of chaotic systems, whereas climate change projection — a “boundary value problem” — does not face any such known theoretical predictability limits, but is difficult nonetheless given the uncertainties in feedbacks, boundary conditions, etc. Some advocates (Robinson and Robinson) have either accidentally or deliberately confused climate with weather and portray both as "initial value problems" bound by chaotic systems. This is unfortunate, as it reduces the public comprehension and distorts the views of decision-makers faced with making climate policy (see “Mediarology”). A Hierarchy of Models. The simplest models involve just a few fundamental equations and a host of simplifying assumptions. A basic global energy balance model, for example, treats Earth as a single point, with no atmosphere and no distinction between land and oceans. The advantage of simple models is that their predictions are easily understood on the basis of well-known physical laws. Furthermore, they produce results quickly and can thus be used to test a wide range of assumptions by simple “tweaking” of the parameters of the model. In a simple energy balance model, for example, the effect of different radiative forcings can be studied by merely subtracting a given forcing from the outgoing energy term to mimic the effect of infrared blockage. More advanced are “multibox” models that treat land, ocean, or atmosphere as separate “boxes” and include flows of energy and matter between these boxes. Two-box models may ignore the land-ocean distinction and just treat Earth and its atmosphere separately. Three-box models handle all three components, but do not distinguish different latitudes or altitudes. Still more sophisticated multibox models may break atmosphere and ocean into several layers or Earth into several latitude zones (see the books by Danny Harvey). Most sophisticated are the large-scale computer models known as General Circulation Models (GCMs). These divide Earth's surface into a grid that, in today's highest resolution models, measure just a few degrees of latitude and longitude on a side. At this scale, a model can represent the actual shape of Earth's land masses with reasonable accuracy. The atmosphere above and ocean below each surface cell are further divided into anywhere from 10 to 40 layers, making the basic unit of the model a small three-dimensional cell. Properties such as temperature, pressure, humidity, greenhouse gas concentrations, sunlight absorption, chemical activity, albedo, cloud cover, biological activity, and so forth are averaged within each cell. Equations based in physics, chemistry, and biology relate the various quantities within a cell, and other equations describe the transfer of energy and matter between adjacent cells. In some cases, separate specialized models are developed for the atmosphere and the oceans, and then linked to make a coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model (A/OGCM). Using such an A/OGCM, Sun and Hansen, 2003 found that in 1951, the Earth was out of radiation balance by about 0.18 Wm-2 and today, that imbalance has increased to 0.75 W m-2. They believe that much of this is the "consequence of deep ocean mixing of heat anomalies and the history of climate forcings." GCMs are time-consuming and expensive to run, and their output can be difficult to interpret. Therefore, GCMs are often used to calibrate or set empirical parameters (those not determined only from fundamental scientific principles) for more computationally efficient, simpler models that can then be used in specific studies, like projecting the climatic responses to a host of SRES scenarios — see the A1F1, A1T and A1B Emission Scenarios figure below. Thus, the entire hierarchy of models becomes useful, indeed essential, for making progress in understanding and projecting climate change. Figure — A1F1, A1T and A1B Emission Scenarios. (Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Synthesis Report, figure SPM-3). Another potential solution for running large model simulations is to elicit the assistance of the public. This is being attempted by a group of scientists led by Myles Allen, who have recently launched a project called climateprediction.net (see a Nature article and a press release announcing the project's official launch). Climateprediction.net was conceived in 1999, when Allen wrote a commentary in Nature titled "Do-it-yourself climate prediction". The project is similar to SETI@home, which uses the personal computers of millions of volunteers to analyze radio signals for possible signs of communication from other inhabitants in the Milky Way. Participants in the climateprediction.net experiment download and run a climate model as a background process on their computers. Each volunteer receives a unique version of the model that will plot out global weather/climate based on that specific set of model assumptions. The results will be sent back to climateprediction.net via the internet, and Allen and his team hope that they will help improve forecasts of climate in the twenty-first century and possibly beyond, by performing statistical analysis on this vast data set he could not otherwise obtain. Many scientists have criticized the climateprediction.net project, saying that it assumes there is no possibility of cooling and that it is simply another model-dependent projection of climate. Allen countered that in a widely circulated e-mail, saying that cooling had not been ruled out, and that was part of the reason for running the experiment. Additionally, he insists that the experiment goes above and beyond traditional climate projections because the comprehensive perturbation analysis (caused by each volunteer having a different version of the model that will produce different results) will establish not only what the model can do, but what it cannot do, no matter how much the parameters change, which is clearly the more difficult task (Allen, 2003). Allen notes that any model constraints found will be applicable to any other system satisfying the same laws of physics encapsulated in these models. Parameterization and Sub-Grid-Scale Effects. One might think that the GCMs would be quite precise since they treat physical, chemical and biological processes more explicitly and at higher time and space resolution. Unfortunately, the partial differential equations that these models contain cannot be solved by any known analytical method; the solutions can only be approximated by breaking the atmosphere or oceans into a finite number of “grid boxes,” or cells, in which all processes are averaged to that scale. Even the best GCMs are limited to cell sizes roughly the size of a small country, like Belgium. But climatically important phenomena occur on much smaller scales. Examples include clouds, which are far smaller than a typical grid cell; and the substantial thermal differences between cities and the surrounding countryside. Because all physical properties are averaged over a single grid cell, it is impossible to represent these “sub-grid scale” phenomena explicitly within a model, but they can be treated implicitly. Modelers use so-called parametric representations, or “parameterizations,” in an attempt to include sub-grid-scale effects in their models. For example, a cell whose sky was, in reality, half covered by fair-weather cumulus clouds might be parameterized by a uniform blockage of somewhat less than half the incident sunlight. Such a model manages not to ignore clouds altogether, but doesn't really handle them fully correctly. You can imagine that the effects of full sunlight penetrating to the ground in some small regions, while others are in full cloud shadow, might be rather different than a uniform light overcast, even with the same total energy reaching the ground (e.g., see Schneider and Dickinson, 1976). Developing and testing parameterizations that reliably incorporate sub-grid-scale effects is one of the most important and controversial tasks of climate modelers (see Danny Harvey's Hard Science or IPCC Working Group I). Hewitson, 2003, too, has acknowledged the need for regional-scale impact assessment, especially in developing countries, and has worked to develop them using "guided perturbations," disturbances to baseline data that are in agreement with the large-scale future climate anomalies predicted by GCMs. His method involves smoothing data from the HADCM3 model (developed by the Hadley Centre for climate prediction and research) and dividing it into "splines", expressing the climate anomaly as the difference between the current and future states of the climate in the splines (after running the HADCM3 model), and perturbing the regional-scale observational data by the amount of the anomaly for the spline in which that region falls. This is an important step in localizing climate studies that will undoubtedly be built upon in the future. The main point for this website is to alert readers about the complexity of using models for regional analyses Transient Versus Equilibrium Models. The SRES scenarios suggest that the atmospheric CO2 concentration is likely to double from its pre-industrial value (that is, reach some 560 parts per million) sometime in the present century. Although it may continue to rise well beyond that, a CO2 concentration double that of pre-industrial times is probably the lowest level likely for stabilizing atmospheric CO2, barring a major breakthrough in low-cost, low-carbon-emitting energy technologies or a major change in philosophy favoring environmental sustainability over traditional economic growth built on cheap fossil fuel burning in the near future. For that reason, and because a doubling of atmospheric CO2 from its pre-industrial concentration provides a convenient benchmark, climatologists often use a CO2-doubling scenario in their models for predicting future climate. The results are typically summarized as a global average temperature rise for a doubling of CO2, and this quantity is taken as a measure of the models' climate sensitivity. As noted earlier, most current models show a climate sensitivity of between 1.5 and 4.5 oC — that is, they predict a global average surface air temperature rise of 1.5 to 4.5 oC for a CO2 concentration double that of pre-industrial times. That is why the IPCC has repeatedly used that range for climate sensitivity. Until the past decade or so, most climatologists did not have sufficient computer power to model the gradual increase in CO2 concentration over time that will actually occur. Instead, they simply specified a doubled CO2 concentration and solved their model equations in a limited simulation to determine the resulting climate. What these so-called equilibrium simulations are actually doing is giving the projected climate that would result if CO2 were instantaneously doubled and then held fixed forever. This is clearly not an accurate representation of how climate change will occur. Transient simulations, in contrast, solve the model equations over and over at successive times, allowing concentrations of greenhouse gases and the climatic response to evolve with time. The result is a more realistic projection of a changing climate. Transient simulations exhibit less immediate temperature rise because of the delay associated with the warming of the thermally massive oceans. In fact, the “transient climate sensitivity” — the warming at the time CO2 doubles during a transient calculation — is typically about half the equilibrium climate sensitivity (see Table 9.1 of IPCC 2001a). And, as noted earlier, the early part of transient responses of the climate to different scenarios of forcing are fairly similar, naively implying that policies to reduce emissions would produce little difference. That reduced rise in the first few decades owing to the absorption of energy in the oceans (among other processes) can be deceptive, because the full equilibrium warming must eventually occur, even if delayed for decades or more. This warming in “the pipeline” will eventually occur, and is often referred to as “unrealized warming.” Transient simulations are essential for modeling climate records like that shown in Earth's surface temperature, which can be drawn, for example, for the CO2 increase of the A1FI, A1T and A1B Emission Scenarios. Recent advances in transient modeling have helped climatologists to better understand the role of anthropogenic gases in global warming. These models can successfully reproduce the climate of the recent past in response to known anthropogenic and natural forcings, which is a testament to their accuracy and ability to predict future climate change (see Models of Earth's temperature). Model Validation. How can modelers be more confident in their model results? How do they know that they have taken into account all climatologically significant processes, and that they have satisfactorily parameterized processes whose size scales are below that of their models' grid cells? The answer lies in a variety of model validation techniques, most of which involve evaluating a model's ability to reproduce known climatic conditions in response to known forcings. One form of model validation has to do with climatic response to volcanic eruptions. Major volcanic eruptions inject so much sulfuric acid haze and other dust into the stratosphere that they exert a global cooling influence that lasts several years and provides good tests for climate models. Such eruptions occur somewhat randomly, but there is typically one every decade or so, and they constitute natural “experiments” that can be used to test climate models. The last major volcanic eruption, of the Philippine volcano Mt. Pinatubo in 1991, was forecast by a number of climate modeling groups to cool the planet by several tenths of a degree Celsius. That is indeed what happened. Figure — Predicted and observed changes in global temperature after the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. (Source: Hansen et al., 1996). The eruption of Mt. Pinatubo graphic above shows a comparison between actual observed global temperature variations and those predicted by a climate model, for a period of five years following the Mt. Pinatubo eruption. Now, a few tenths of a degree Celsius is small enough that the observed variation just might be a natural fluctuation. However, earlier eruptions including El Chichón in 1983 and Mt. Agung in 1963 were also followed by a marked global cooling of several tenths of a degree Celsius. Studying the climatic effects from a number of volcanic eruptions shows a clear and obvious correlation between major eruptions and subsequent global cooling. Furthermore, a very simple calculation shows that the negative forcing produced by volcanic dusts of several watts per square meter is consistent with the magnitude of cooling following major volcanic eruptions. Viewed in light of these data, the graph above suggests that climate models do a reasonably good job of reproducing the large-scale climatic effects of volcanic eruptions. Seasonality provides another natural experiment for testing climate models, as noted earlier. Winter weather typically averages some fifteen degrees Celsius colder than summer in the Northern Hemisphere and five degrees colder in the Southern Hemisphere. (The Southern Hemisphere variation is, as explained above, lower because a much larger portion of that hemisphere is water, whose high heat capacity moderates seasonal temperature variations.) Climate models do an excellent job reproducing the timing and magnitude of these seasonal temperature variations, although the absolute temperatures they predict may be off by several degrees in some regions of the world. However, the models are less good at reproducing other climatic variations, especially those involving precipitation and other aspects of the hydrological cycle. Of course, reproducing the seasonal temperature cycle alone — since these variations come full circle in only one year — does not guarantee that models will accurately describe the climate variations over decades or centuries resulting from other driving factors such as increasing anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations. However, the fact that models do so well with seasonal variations is an assurance that the models' climate sensitivity is unlikely to be off by a factor of 5 - 10, as some greenhouse “contrarians” assert. Yet another way to gain confidence in a model's ability to predict future climate is to evaluate its accuracy in modeling past climates. Can the model, for example, reproduce the temperature variations from 1860 to present charted in Variations of the Earth's surface temperature? This approach not only provides some model validation, but it also helps modelers to understand what physical processes may be significant in determining past climate trends. The figure, Models of Earth's temperature, shows three different attempts at reproducing the historical temperature record of the Variations of the Earth's surface temperature (a) using the same basic climate model. In Models of Earth's temperature (a), only estimates of solar variability and volcanic activity — purely natural forcings — were included in the model. The model's projected temperature variation, represented by a thick band indicating the degree of uncertainty in the model calculations, does not show an overall warming trend, and clearly deviates from the actual surface temperature record. In Models of Earth's temperature (b), the model included only forcing due to anthropogenic greenhouse gases and aerosols (e.g., the CO2 record of Indicators of human influence (a), along with other known greenhouse gases and particulate emissions). This clearly fits the actual temperature change line much better, especially in the late twentieth century, but it deviates significantly from the historical record around mid-century. Finally, Models of Earth's temperature (c) shows the results of including both natural and anthropogenic forcings in the model. The fit is excellent, and suggests that we can increase our confidence in this model's projections of future climate. An examination of all three variations of the model strongly suggests that the temperature rise of the past few decades is unlikely to be explained without invoking anthropogenic greenhouse gases as a significant causal factor. Thus, these “experiments” are illustrative of one way of attempting to pry an anthropogenic climate signal from the natural climatic noise. Moreover, the Models of Earth's temperature provides substantial circumstantial evidence for a discernible human influence on climate and for the 2001 IPCC report's conclusion that “…most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities”. Incorporating the role of aerosols into GCMs also improved their accuracy. As Weart mentions in the section of his website dealing with GCMs, GCMs typically produced a climate sensitivity of about 3 oC, but the actual rise in temperature did not seem to be keeping pace with the rise in CO2. Once the cooling effect of aerosols was accounted for, the GCMs could recreate historical temperature changes accurately. Today's climate models provide geographical resolution down to the scale of a small country. Not only can they reproduce global temperature records, as shown in the Models of Earth's temperature, but the best model results approach, although with less accuracy, the detailed geographical patterns of temperature, precipitation, and other climatic variables. These “pattern-based” comparisons of models with reality provide further confirmation of the models' capacity to simulate important features of the climate. For example, recent work by Root et al. (in preparation) shows that plants and animals are responding in a statistically significant way to anthropogenic climate changes produced by the GCM used in the Models of Earth's temperature figure. This is strong circumstantial evidence that GCM regional forecasts driven by forcingscan be skillful — again, see the Models of Earth's temperature figure. This is an independent validation of GCM regional projections that, because plants and animals are proxy, not instrumental records, avoids all the claims about "faulty thermometer" data sets by some contrarians. (More on the details of this in Winter, 2004). No one model validation experiment alone is enough to give us high confidence in that model's future climate projections, since the anthropogenic radiative forcings projected to 2100 are different than any known in the past, and there is no direct way of empirically testing the model's performance — except to wait until the Earth's climate system performs the "experiment”. [Whether to take that risk is what the climate policy debate is about (see Laboratory Earth).] But considered together, results from the wide range of experiments probing the validity of climate models give considerable confidence that these models are treating the essential climate-determining processes with reasonable accuracy, and we can therefore expect them to produce moderately realistic projections of future climate, at least at the large scale, given credible emissions scenarios. We do still expect variations in the projections of different models, and because future greenhouse gas emissions depend on human behavior, future projections will differ depending on what assumptions modelers make about the human response to global warming. The uncertainties in projections of human behavior cause about as much spread in estimates of future warming as do uncertainties in our understanding of the sensitivity of the climate system to radiative forcings. We will probably have to live with this frustrating situation for some time to come. Estimating a Range for Climate SensitivityDecision Analytic Survey. In a Morgan and Keith survey (see Morgan and Keith), sixteen scientists were interviewed about their subjective probability estimates for a number of climate factors, including climate sensitivity (i.e., the increase in global mean temperature for a doubling of CO2). The Morgan and Keith survey shows that although there is a wide divergence of opinion, nearly all scientists assign some probability of negligible outcomes and some probability of highly serious outcomes (see the Estimates of climate sensitivity below). Note that one scientist, Richard Lindzen of MIT — expert 5 on the figure — believes (or believed in 1994) that there is essentially no chance of warming much beyond 0.5 oC for doubling CO2 — an opinion radically different than the other 15 climate scientists Morgan and Keith interviewed. Expert 9, for example, responded that he believed there was a five percent chance of warming below about a degree Celsius, a fairly high probability that warming would be in the IPCC range of 1.5-4.5 oC, but also a disquieting chance — about 5% — that warming of greater than 6 oC could occur. Having been Expert 9, I can explain the reasoning behind the projection that there's a five percent chance that climate sensitivity will elicit 6 oC or more of warming: cooling from aerosols could have masked recent warming that otherwise would have been realized and rapid climate change could possibly trigger major nonlinear events like rapid disappearance of sea ice over the long term. As sulfate aerosol levels decline, we could see a very large climatic response to greenhouse gas forcing — an opinion also expressed in the Estimates of climate sensitivity by most of the climate scientists surveyed. Of course, new data on non-sulfate black carbon aerosols will add yet further complications not yet quantifiable with even medium confidence. Figure — Subjective Estimates of climate sensitivity. (Source: Morgan and Keith). Estimating Climate Sensitivity Empirically. Given the uncertainties inherent in the feedback processes that must be incorporated into climate models, is there any way to estimate climate sensitivity empirically? In fact, there are two ways. One is to use historical paleoclimatic situations in which both forcing and temperatures were different than the modern era. Hoffert and Covey have attempted this estimation, performing an analysis using reasonable assumptions, and have arrived at a climate sensitivity in the range of 2-3 oC for a doubling of CO2. Of course, precise forcings and temperatures are not available for the distant past, so an uncomfortable degree of uncertainty exists in such empirical attempts. Nevertheless, they do add confidence that current ranges of climate sensitivity are not wildly unrealistic. Moreover, we must use transient simulations when comparing to temperature records of the past few decades. More precise information on both temperature trends and radiative forcings exist for the past 50 years. But, as the figure, Global mean radiative forcing, has shown, there is still considerable uncertainty in estimating radiative forcing, mostly because of the unknown related to the indirect effects of aerosols. If one were to estimate climate sensitivity by tracking how much warming occurred over the past 50 years and scaling this warming by the amount of radiative forcing caused by greenhouse gas increases, a ratio of temperature rise to forcing — i.e., climate sensitivity — could be estimated. If there were no anthropogenic aerosols, then the greenhouse gas forcing of about 3 Watts per square meter would represent warming of about 0.6 oC. But if aerosols reflected an average of about 1.5 W/m2 back to space, then the climate sensitivity that we would estimate would be twice as large since the observed warming would have been scaled by only a net forcing of 1.5 W/m2 rather than 3 W/m2 for greenhouse gases alone. Thus, to empirically estimate the climate sensitivity, all the forcings need to be estimated and aggregated to find the net overall forcing number, meaning there will continue to be a very large range of uncertainty associated with estimates of the all-important climate sensitivity parameter. In fact, uncertainty in radiative forcings is at least a factor of three. Again, only transient comparisons are legitimate. Andronova and Schlesinger (their website), for example, attempted to create a broad probability distribution for climate sensitivity by scaling the observed temperature trends against a range of possible forcings. Because of the uncertainties in forcing, they get a very broad distribution, as seen in the Single probability density function, below. About 50% of the estimates for climate sensitivity lie outside of the IPCC's 1.5 to 4.5 oC range. Moreover, other groups have attempted semi-empirical estimation of climate sensitivity, obtaining similar results to Andronova and Schlesinger (see Figure 4 of Forest et al., 2001, and Webster et al., 2003). Thus, despite the relative stability of the 1.5 to 4.5 oC climate sensitivity estimate that has appeared in the IPCC's climate assessments for two decades now, more research has actually increased uncertainties! Of course, it is likely that the very wide range in the Single probability density function below will be narrowed as we continue to measure the world's temperature and monitor the forcings. But in my view, it will take decades to pin down the climate sensitivity to even a factor of two. Thus, while the Single probability density function suggests that we will most likely not have to cope with a climate sensitivity of over 3 oC, the ten percent chance of a sensitivity of 6 oC or more is of large concern, and, in my opinion, cannot be ignored by citizens or policymakers concerned with minimizing risks to environmental sustainability. If there were 'only' a 10% chance that there were salmonella bacteria in your salmon dinner, would you eat it? In support of such concern, Caldeira et al. (2003) believe that unless climate sensitivity is on the low end of estimates, “climate stabilization will require a massive transition to CO2 emission-free energy technologies " Figure — Single probability density function (pdf) and cumulative density function (cdf) pair for climate sensitivity, delta T2x, the equilibrium surface temperature warming for a doubling of CO2 (source: Andronova and Schlesinger). See also:

Links

|